By T. D. Thornton

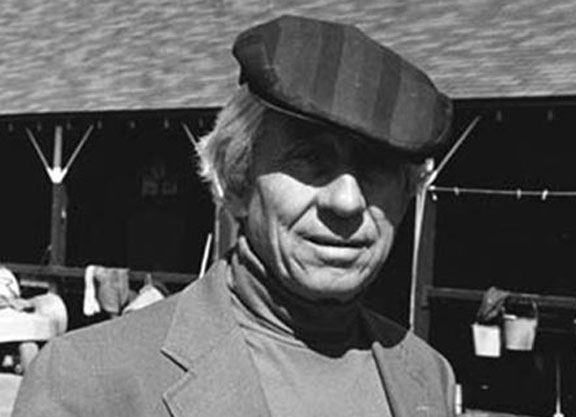

Remembrances and condolences poured in from all corners of the racing world on Thursday in the wake of news that the sport lost one of its oldest living legends: John A. Nerud, 102, died from heart failure at his home Old Brookville, N.Y., in the early hours of Aug. 13.

Nerud's death was confirmed by the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame, which inducted him in 1972.

Nerud's life with horses spanned an improbable, but highly respected and successful career arc. He rose from the ranks of ranch hand to rodeo cowboy to stable groom; to jockey and jockey's agent, and to eventual prominence as a trainer, owner, breeder, and co-founder of the Breeders' Cup.

But it was Nerud's class, tenacity, and down-to-Earth demeanor that shone through to generations of racing industry participants, earning him the unofficial title of “trainer of trainers” for his willingness to take under his tutelage up-and-coming conditioners who showed promise and respect for the horse.

A number of those horsemen–like Flint S. “Scotty” Schulhofer and D. Wayne Lukas–later joined Mr. Nerud in the Hall of Fame. In turn, those trainers' own subsequent generations of proteges and assistants seem destined for the Hall of Fame, thanks to lessons passed down from Nerud.

Another Hall of Famer in that group is Carl Nafzger, who trained GI Kentucky Derby winners Unbridled (1990) and Street Sense (2007). Nafzger recalled trying to get established in the racing business at Saratoga in 1981 when he first met Mr. Nerud, who was then overseeing the sprawling Tartan Farms racing and breeding operation. The two hit it off, and a few months later, Nafzger got his first big break when Mr. Nerud sent him a string of horses to train at Oaklawn Park.

“I can only say one thing about Mr. Nerud: It was an absolute honor, privilege and blessing to be able to work under him and work with him,” Nafzger said. “He was an unbelievable horseman. He understood the whole scope of the horse. He knew exactly where a horse was in his training, what that horse could do, and where he was going with him. And if you worked for him, you'd better be able to answer those same questions. If you didn't understand the horse, you didn't work with Mr. Nerud for very long.”

Michael Hernon, currently the director of sales Gainesway, recalled meeting Nerud a bit later in life, when Hernon was with Fasig-Tipton and the sales company was handling the Tartan-Nerud dispersal in 1987. A $70,000 weanling sold at that dispersal ended up being Unbridled. Hernon and Mr. Nerud subsequently worked together when another champion that Mr. Nerud bred and raced–Cozzene–stood at the nursery.

“He was a consummate horseman. He was a very quick study. He was articulate. Yet he was a 'regular guy,'” Hernon said. “Mr. Nerud accomplished great things. He was a horseman from the ground up, and he left his own indelible mark on the business, broadly speaking.”

Nerud was born Feb. 9, 1913, and grew up as one of nine children in Minatare, Nebraska. According to a family legend, at age five he received a horse from his father. At 13, young John became lost in a blizzard while riding “Old Red” to care for cows on the family ranch. He turned the horse loose, knowing that by instinct it would lead him back home. In retelling that tale to the New York Times this past June, Nerud credited that horse with saving his life.

According to his Hall of Fame bio, Nerud was the agent for jockey Ted Atkinson in New England prior to serving in the Navy in World War II. After serving his country, her returned to racing as an assistant to Frank J. Kearns at Woolford Farm. He eventually took over from Kearns and in 1949 trained his first elite-level horse, Delegate, who was named co-champion Sprinter.

Although he saddled over 1,000 winners and 27 stakes winners, Nerud was also known for grace in defeat. In 1957, he lost the Kentucky Derby by a nose when jockey Bill Shoemaker misjudged the finish and stood up in the irons aboard Gallant Man in the shadow of the wire.

“You can't turn the clock back,” Mr. Nerud reminisced to the New York Times 58 years after the incident. “What are you going to do? If you're a gentleman, you say nothing; you eat it and go home.”

Several weeks later, Gallant Man set a track record in winning the Belmont S., defeating Bold Ruler by eight lengths. The mark stood until Secretariat surpassed it with a world-record clocking for 1 1/2 miles in 1973.

Nerud's most acclaimed runner was Dr. Fager, who in 1968 became the only Thoroughbred to win four championships in one year (Sprinter, Turf Horse, Handicap Horse, and Horse of the Year).

But Nerud almost died before the “world's fastest horse” (as Dr. Fager was known in that era) ever made it to the races. In 1965, when he sustained a near-fatal head injury after being thrown from his lead pony, famed neurosurgeon Dr. Charles Fager saved his life with an emergency operation. Nerud expressed his gratitude by naming his most promising colt in the doctor's honor.

On the occasion of Mr. Nerud's 100th birthday party in 2013, Jeff Fager, the son of the renowned surgeon, said, “From all the people my father operated on, and he saved a lot of people, he got a lot of fruitcakes and chocolates. But he never got a champion racehorse named after him.”

In addition to Delegate and Dr. Fager, Nerud also trained champions Intentionally (1959 Sprinter) Ta Wee (1969, 1970 Sprinter) and Dr. Patches (1978 co-Sprinter). When he retired from training in 1978, he stayed on at Tartan as manager of racing and breeding.

During the early 1980s, Nerud assisted in the development of the Breeders' Cup, helping to sell the concept to horsemen across the nation. In 1985, he won the GI Breeders' Cup Mile with his homebred Cozzene, who was trained by his son, Jan.

Beyond his many public accolades, Mr. Nerud was quietly and privately recognized for his help in assisting hands-on horse workers and for his efforts to improve backstretch conditions. On Thursday afternoon prior to saddling a horse at Saratoga, trainer Mark Hennig related a story that typified Nerud's generosity: About six years ago, Hennig was asked by a racing publication to name the person in the sport he would most like to have dinner with. Although he had only met him briefly in the past during his time as an assistant to D. Wayne Lukas, Hennig didn't hesitate to answer “John Nerud.” Hennig said that about a week after the article came out, he got a call out of the blue from Nerud himself, extending an invitation to come to his home on Long Island for dinner.

“I was kind of shocked,” Hennig said. “My wife and I went, got the tour of his house, saw all of his trophies. It was like a museum. He told a lot of neat stories. It was just one of those experiences that you'll never forget. It was amazing at how crisp his mind was, even at that age. He was a really unique man, the type that we'll probably never see again. At least not in my lifetime.”

Nerud was married to his wife Charlotte for 69 years before her death in 2009. He is survived by his son Jan, daughter-in-law Debra, and grandchildren. Funeral arrangements are pending.

In 2013, Nerud was asked in a Q &A piece by the New York Times how he would like to be remembered.

“I'd like to be remembered as just plain John Nerud,” he said. “I never got high on myself. I never looked for [recognition] and I was very outspoken. I never broke the rules. I never was fined. I never had a 'tester.' I never had a ruling made against me in my whole life. I probably did some things I should've been fined for, but I didn't get it. I raced my horses and I abided by the rules and didn't try to be any better than anybody else. I'm just John Nerud—a country boy. And I still am.”

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.