By Bill Finley

There are only a few things that are certain about the 1968 Kentucky Derby. Dancer's Image, owned by New England car dealer Peter Fuller, crossed the finish line first. He would later be disqualified and placed last after chemists performing post-race tests from that day determined that the colt had traces of the then illegal medication phenylbutazone in his system. Saturday's GI Kentucky Derby will be the 144th renewal of the race and Dancer's Image remains the only horse to have ever been disqualified after an apparent victory.

There's obviously much more to the story, but every other detail leads down a road that dead-ends in a mystery. Virtually no one believes that Fuller or trainer Lou Cavalaris, two individuals who never had a hint of scandal in their careers before or after the Dancer's Image Derby, conspired to dope their horse to win the race. How then, did the Bute get into the horse's system? Or, perhaps, was the disqualification the result of a botched or tampered test? With so much time having passed and with most of the people involved in the story having died, these are questions that likely will never be answered.

“It has bothered me to this day,” said journalist Billy Reed, who as a 24-year-old reporter in 1968 for the Louisville Courier-Journal covered the story. “Nobody, really, has ever definitely been able to say this is what happened.”

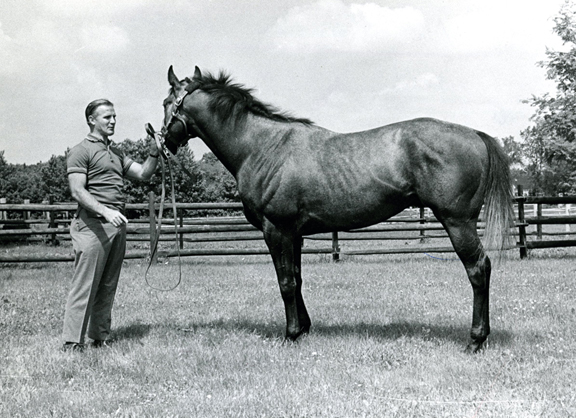

Coming off a win in the Wood Memorial, Fuller's homebred son of Native Dancer was considered one of the horses to beat in the 1968 Derby. On the advice of another of his trainers, Odie Clelland, Fuller decided to stable the horse in the barn of Dr. Alex Harthill, one of the most talented and controversial vets in racing history. In a different era in the sport, Harthill was such an influential veterinarian that not only did he have his own office on the backstretch at Churchill, but he had his own barn.

It was hardly a surprise that Harthill was brought into the fold as he was widely known as the “Derby Doc.” Upon his death in 2005, it was reported that Harthill had said he had treated 26 Kentucky Derby winners, starting with Citation in 1948. Dancer's Image also came out of the Wood Memorial with ankle problems and Harthill was considered the very best there was when it came to finding ways to get horses over whatever was ailing them and ready for a race.

Everyone involved acknowledges that Harthill gave Dancer's Image a shot of Bute six days before the race, but that should have been plenty of time for the drug to be completely out of the horse's system by Derby Day. The next six days seemed to be routine ones. Dancer's Image was in top form for the Derby and, sent off at 7-2 in the wagering, crossed the wire 1 1/2 lengths in front of Calumet Farm's Forward Pass.

For Fuller, Cavalaris, jockey Bobby Ussery and everyone else that was part of the Dancer's Image team, the celebration did not last long. The chemists working for the Kentucky Racing Commission reported that the post-race test on Dancer's Image came up positive for Bute. By the Monday after the Derby, Cavalaris and Fuller were informed that their horse was disqualified and placed last.

“The words staggered me,” Cavalaris told Sports Illustrated in 1968. “I was spellbound. I just stood there. I've been in this game 21 years and I've never done anything wrong. I'm innocent, and so are my men. They love Dancer's Image, just as I do.”

Fuller was also staggered, but he fought back, taking the matter to the courts, basing his case on his belief that Dancer's Image did not have anything illegal in his system and that the test was botched. It's unclear if he believed that was the case or that someone tampered with the horse, but the latter allegation would have been much harder to prove. Getting to the bottom of what really happened was made more difficult by the rules that were in place in 1968. No split samples were made available and never was the level of Bute in the horse's system recorded. There were no allowable threshold levels then, so any amount of the medication in Dancer's Image's system would have resulted in a positive.

Fuller, who died in 2012, told reporters he spent $250,000 in legal fees fighting to regain his Kentucky Derby win, but five years after the race, he had exhausted all legal maneuvers and Calumet was paid the winner's share of the Derby purse.

“Until the day he passed, it still haunted my father,” said Abby Fuller, who was nine in 1968 and went on to win Grade I races for her father as the jockey of Mom's Command. “I think he wanted the story and whatever the truth was to come out. I don't know if anyone who is alive knows the whole truth. We all have our ideas and there are little pieces and things that we have all heard. But it's still a mystery.”

The sexier theory is that someone “got to” Dancer's Image, but Milt Toby, the author of “Dancer's Image: The Forgotten Story of the 1968 Kentucky Derby” believes those who performed the post-race tests simply could have gotten it wrong.

“The evidence in the very lengthy racing commission hearing at end of 1968 seemed to me to be compelling that there was a problem with the test,” he said. “But it wasn't conclusive. The difficulty with that assumption that the test was wrong is that, even if the techniques were not reliable and the chemists was not credible and there were problems over the years with the lab, that doesn't mean that all the results over the history of this chemist and this lab were wrong. That doesn't mean this particular test was wrong.”

If the test was correct, what happened?

Other than the Bute dosage Dancer's Image received six days before the race, no one ever admitted to giving the horse the drug at any other time leading up to the race. And had someone done so, they surely would have known that there was a high degree of likelihood they would be caught if the horse won the race. Then there was Fuller's reputation. He was considered a man of the highest integrity.

“I grew to have a lot of respect for Peter Fuller,” Reed said. “He was an honest, decent guy who got a really bad deal. Peter Fuller was such a good person. He deserved to win the Kentucky Derby.”

So it was left to journalists like Reed and his colleague at the Courier-Journal at the time, the late Jim Bolus, Fuller and his lawyers to dig around in an attempt to find out what happened.

Many of the theories that have evolved over the years center around Harthill.

“In my personal opinion, I will always believe that Dr. Alex

Harthill is certainly the villain of this story,” Reed said.

In Harthill's obituary in the Daily Racing Form, author Marty McGee summed up the more controversial aspects of the veterinarian's life and career.

“Although his legacy as a practicing veterinarian was sealed early, Harthill quickly became synonymous with controversy and seemed to live on the edge of racing legality,” McGee wrote. “Intense speculation long has swirled about his role in the disqualification of Dancer's Image, who tested positive for Butazolidin, an anti- inflammatory drug that was banned at the time. He was arrested in the 1950's in Louisiana for allegedly bribing a testing laboratory employee. He was persona non grata in recent years in New York, and he was a central figure in countless racetrack controversies and court cases in Kentucky and elsewhere.”

But if Harthill purposefully treated Dancer's Image with Bute in close proximity to race time, what would have been his motivation?

“Harthill had treated all of Calumet's horses, going all the way back to Citation,” Reed said. “And, certainly, Forward Pass was an overwhelming favorite with the Kentucky hardboots that year.”

Reed's dealings with Harthill took a bizarre turn when the reporter was sent by his editors to the Churchill backstretch after the disqualification to get a better lay of the land. Reed said Harthill came up to him, grabbed him and punched him. Harthill admitted he hit Reed.

“I was stunned,” he said. “I was laying there, he was standing over me and I remember him saying to me, 'You've been checking into that gambling coup at Caliente, haven't you?' I had never heard of the Caliente future book at that time.”

Reed said he went to Mexico to investigate whether or not there had been any unusual betting on the Derby winterbook that year, but did not find any evidence that there was.

Another popular theory is that the events that led to Dancer's Image's disqualification were a payback to Fuller, a liberal New Englander and a civil rights advocate. Following Dancer's Image's win earlier that year in the Governor's Purse at Bowie, Fuller took his winnings from the race and gave them to the widow of Martin Luther King Jr., who was assassinated Apr. 4, 1968.

“There were a lot of racial undertones at that time,” Abby Fuller said. “After he made that donation to Dr. King's wife, he got a lot of threatening letters. He wanted to bring in his own guys for security and Churchill told him no, that that would only make it worse.”

Reed has never been a believer in the theory that the King donation had anything to do with the Derby.

“I've never given any credence to theory that this happened because Peter Fuller had given one of the purses from a win to the widow of Dr Martin Luther King Jr.,” he said. “People think that all these redneck racists from Kentucky were out to get this liberal from New England. I don't buy it.”

Toby has another theory on Fuller's relationship to the King family.

“The intriguing argument that most people have dismissed over the years is that his donation of the Governor's Gold Cup purse to Coretta Scott King actually had an effect or influence of some kind, but, perhaps not with people in Kentucky,” he said.

“During those times, J. Edgar Hoover was fighting a battle against Martin Luther King and everyone supporting him. It would be interesting to see if there are FBI files that Hoover kept on Peter Fuller.”

Dancer's Image raced just one more time, crossing the wire third behind Forward Pass in the Preakness. Ironically, he was disqualified again, this time for bumping another horse. He was placed eighth. After an undistinguished career at stud, he died in Japan in 1992.

Fuller was never the type of owner who had a large and powerful stable, so he had to wait for his next “big” horse. That was Mom's Command. She was the champion 3-year-old filly of 1985 and was later enshrined in the Hall of Fame. That story was made that much sweeter by the fact that Fuller's daughter was her regular rider. But Abby Fuller said Mom's Command's success was not enough to erase the pain that still burned inside his father over the Dancer's Image situation.

“He never got over it,” she said. “People always said, 'Didn't Mom's Command make up for it? She was amazing and wonderful, but she was her own thing.”

On this, the 50th anniversary of the 1968 Kentucky Derby, the record book says that the winner that year was Forward Pass.

Reed, for one, will never accept that. He is not alone.

“One of my prized possessions is a picture of Dancer's Image being led into the winner's circle,” Reed said. “Peter Fuller is on one side, Lou Cavalaris is on the other side and you can see me right behind them. I've always cherished that picture. Even though Forward Pass's name is up there as the winner, I will always consider Dancer's Image to be the winner of the 1968 Kentucky Derby.”

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.