By Chris McGrath

“Everyone can be fooled by a horse,” he says. “You see the young oozing of talent, you buy him, and it just doesn't work out.”

So far, so familiar. You'd hear as much from any number of professionals in our business, humbled by the unpredictability of the Thoroughbred. Not many people, though, would follow up with a remark as acute and original as the one offered next by Dr. Barry Eisaman: “But if it was as easy as not being fooled, everyone would have a Derby horse every other year.”

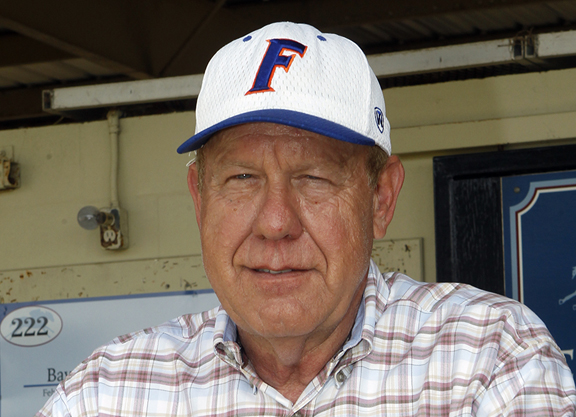

He is sitting on a deck overlooking the training track, the air drowsy with the warm thrum of insects and birds. It really is a very special setting: an optimal blend between the teeming abundance of nature, a few miles upcountry from Ocala, and the harmonious interventions of man: the railed circuit, the immaculate paddocks and barns, this command post. But there's nothing dreamy about the gentleman in front of you, with his methodical, contained demeanour; his even, considered delivery.

At the moment, Eisaman happens to be talking about the synthetic surface at OBS, where the yearling pinhooks developed here tend to be sold every spring. He dislikes the way some agents tend to take refuge in the surface when a purchase doesn't pay off; the way they talk about having been “fooled.” That's too easy, he complains. It disposes too glibly of the multiple factors that contribute to the fulfilment of a Thoroughbred.

“If you depend entirely on a numerical time to separate them, yes, they are somewhat bunched,” he accepts. “But then the horsemanship kicks in. Every :10 flat work is not created equal. If you watch them, there's a separation.”

The bottom line, he says, is that no matter how honestly and diligently people go about buying horses, this is and always will be a subjective business. A horse might be fooling you for far longer than 10 seconds.

And that's just why we're here, borrowing insights from a master of a cycle just now being renewed across the industry–the breaking and preparation of yearlings, both for the sales and for his clients' racetrack trainers. Many of the first group will have been scouted by Eisaman's wife Shari. But their yearling program also dovetails with a parallel service for older animals, returned from the track in need of physical or mental retuning.

Eisaman, as such, can claim two new Breeders' Cup laureates in migrants Blue Prize (Arg) (Pure Prize) and Uni (GB) (More Than Ready). Blue Prize spent her first four North American months here, learning to become a good U.S. citizen; while Uni has been here for two vacations of sunshine and pasture, when spelled from training.

In fact, Eisaman Equine had a total of four graduates at the Breeders' Cup, and they ran 1-1-2-3. Both GI Classic runner-up McKinzie (Street Sense) and GI Juvenile Fillies third Bast (Uncle Mo) had come here as yearlings to be broken, and to learn how to be a racehorse. Just getting four individual Grade I winners to the meeting is extraordinary, never mind for them all to run so well.

It's a diverse operation, then, and on a fairly industrial scale: the Eisamans typically break 170 yearlings. But their eye for nuance is such that one of the market's most successful dealers commends them as “the smartest couple in the American horse business.”

They have been here for 20 years now. In that time, they have developed a model that achieves a reliable balance between a necessary delegation and the fulcrum of that critical, subjective eye, alert to every variation in horses' response to their schedule.

The delegation extends through four principal barns, each with manager and crew, all working off a database updated daily by Eisaman, their assignments checked off by his assistant on entering the track. Such a flux of activity depends on trust–both in the system, and in its operatives.

“Basically, that system revolves around breaking horses without using aggressive techniques,” he explains. “If you're an experienced horseman, you can mostly finesse your way through difficult times without having an argument about it. In a quiet way, you make this change or that change, and you teach that young horse something. So excessive stick use, excessive yelling, excessive language don't really have any place in our world. And the riders here know that.”

As Eisaman wryly concedes, there will be “a couple of criminals” in every crop who don't respond to that finesse; usually colts, usually on their way to becoming geldings. But the aspiration is to lay down a foundation of day-by-day, quietly incremental challenges. And that's where the skill comes in: to know when to take them somewhere new, but also to know when straining becomes stress.

“From doing it so many years with so many horses, I have a pretty good idea of how long they need to be at each level before we go up,” Eisaman says. “Early on, when they first go to the racetrack, they're going in company, so they have a friend. And they're basically just jogging, just getting to see things and make their way around. Then after they perfect doing that–maybe that's two weeks, maybe three–they begin to turn left, jogging the wrong way. That allows them to see oncoming traffic. Most don't mind, but there's a small percentage that really are very afraid.”

And so it proceeds. Next a more purposeful gallop; a look at the big gate. They've already become accustomed to a walk-through, two-stall, PVC baby gate, to its harmless creaking, from day one.

“Though we try not to rush them through any of these levels,” Eisaman stresses. “You build a racehorse little by little. Every day they're doing what they're going to do for a living. They're creatures of repetitive learning. Do something often enough, it becomes second nature. So when they go to the racetrack, they'll say, 'Oh, this is no big deal. I've seen this before.'”

So how reliably can he pick out the star pupil from these cumulative exam results?

“The ones that impress me are those that show class with their mentality, as they learn,” he reflects. “They don't have an argumentative nature. But classy ones also tend to be healthy. They're tough. They don't have filled joints. If there's a cough going around, they don't get it. And every time they get increased to another level of work, they're like, 'Nothing to it. What's next?'

“But even then, you never know for sure until they're in the gate with 10 or 12 horses. Some that have been star pupils the whole way, they get bumped around a few times and say, 'Oh, I didn't bargain for this.' And they don't follow through and make their talent count.”

That said, Eisaman finds that the “prince” will pretty reliably turn out to be a runner-even if there will also be the occasional “frog” that transforms under the starter's kiss.

“That is not the usual scenario,” he concedes. “But it's the subjective nature of our whole sport that makes it so interesting. You can't say that every frog's a dud. And vice versa.”

Despite the high stakes of a 2-year-old auction, Eisaman says that his sales and racetrack programs are essentially the same: identical, in fact, for the first 100 days. Whether the horses come direct from the farm or from the sales ring, he only gives them a couple of days to confirm their health before introducing them to his regime: he finds them more attentive, that way, than if given a couple of idle weeks getting fresh.

The two groups do their 14- and 13-second eighths together, and only then will the sales horses be asked to sharpen up for their breeze. At Eisaman Equine, they comprise only around half the number of the group heading to the track.

“But it's how we started and still is the major profit area of our whole business,” he says. “Breaking horses to go to the races, over the years, for us has been as much about maintaining relationships and contacts as anything. If you're trying to do a really good job, and not cut any corners, it's not a hugely profitable venture. But it keeps me in daily contact with some of the best trainers in this country, and in a confidence-building relationship. So that also then helps us sell horses. When I'm asked about a horse, everyone that knows us will know we're about a long-term relationship and not trying to mislead anyone. We get a very high level of repeat customers.”

Some of those trainers will also send horses here for rehab or treatment, with many diagnostic and surgical facilities to hand and Eisaman himself having started out as a veterinarian. Often he is sent the mystery cases, with some elusive unsoundness, and enjoys teasing out the solution. He compares his role, in prognosis and the commissioning of treatments, to that of a quarterback.

“I might have multiple cases going on at the same time where I'm at the apex of the decision-making, but not necessarily doing all the hands-on stuff every moment,” he says. “It's like solving riddles, playing chess. It would be very hard for anyone to do in a racetrack setting, and it's enjoyable for me.”

His vocation traces to a childhood in Western Pennsylvania, where his parents had a boarding stable for pleasure and show horses. He was first pointed to Florida by tutors at the New Bolton Center at the University of Pennsylvania, who knew of an opening at a Miami practice.

“I'd never really thought about leaving Pennsylvania,” Eisaman admits. “But we had two feet of snow on the ground, and here was an all-expenses trip to Miami for the weekend. I ended up working with them for seven or eight years: a racetrack and farm practice under Dr. Teigland: one of the founding members of the AAEP in the '50s, and a wonderful, wonderful man.”

The young Eisaman obviously made quite an impression on the trainers in Miami, because when he moved to Marion County they started sending him their lay-ups. And he certainly made the impression on the daughter of one of his new clients: she became his partner in life and business. Shari had been buying and selling horses even as a teenager and, combining their expertise, the Eisamans for many years became leading vendors at the OBS March Sale. Commercial pinhooking, however, has become tougher game over recent times.

“Shari is probably the best horse buyer I've ever been associated with,” he says. “For years, we would be able to go to the sale and buy a nice $50,000 yearling that really had a stout amount of pedigree, that we could break and take to the 2-year-old sales and sell for a modest profit. We were never of the mindset to invest high dollars in a yearling to shoot for a million-dollar horse. We wanted, over and over again, our model of a nice horse and, over the years, we sold many, many stakes horses that way.

“But in recent years, the whole foal crop has decreased, and there's so many people pinhooking, it almost needs a different term. Because it's not what it once was. You have groups of people putting together money, sometimes not even groups of individuals but groups of groups. With the strength of the stock market and hedge funds, a lot of money has been emptied into buying to re-sell. So for us–for the most part doing it solo, with occasional partners to help us along the way–competing with those bigger, extremely well-funded entities, we're just not able to buy the same quality of horse as 10 years ago.”

They fight their corner by seeking enough pedigree to get a horse noticed, while making sure that anyone who does come and look will be greeted by an athlete. Like so many, Eisaman is disenchanted by the market's growing enslavement to the clock.

“We've become so trapped by times that we're asking horses to do something they're never going to have to do in their life again,” he objects. “And all the rest of the horsemanship is taking a back seat. Yet, if you look historically, those kind of acid-speed, :9 4/5 works will rarely translate into a potential Classic runner. They're first-out winners, they're quick, they're sprinters. The two-turn horses, their times might be a tick slower, but when they get moving, at a :10 2/5, :10 3/5 speed, they cruise out like a big jet liner and just keep going.”

And so, too, do the Eisamans, dovetailing their personal and professional lives. Another yearling sale season over, the next round of the carousel underway–and none of the many people engaged in the tuition of adolescent Thoroughbred, in Florida and beyond, will have greater respect across the professional community.

“We never stop working,” Eisaman says. “Fortunately, we both have a passionate love for the Thoroughbred horse and for this sport. Our vacations are the Keeneland yearling sale. We don't always see eye-to-eye on every horse, or on what we're going to do. But we have been able to make decisions together our entire life. If we win, we win. If we don't, we don't. But being able to do this for a living, together, it's been a lot of fun.”

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.