By Chris McGrath

What is it, beyond our obvious bond in the Thoroughbred, that most vitally comprises the fabric of the Turf?

It's a question answerable in too many ways, requiring definition of too many intangibles, to be easily condensed. But I think we'll get somewhere close if we ponder the retirement this week of Stan Hough, an old-school horseman of a type largely overwhelmed in the era of the super-trainer. And especially because his departure from the stage coincides with the removal of two key features of the scenery: Calder Race Course, where Hough won five consecutive training titles from 1976; and Sagamore, his final patron, now being disbanded as a Thoroughbred farm.

For three such names to recede simultaneously from our sporting theater is surely a prompt to reflect on those elements in our heritage as precious as they are liable to slip through our grasp.

That is not to invite any conflation of the factors determining each of these withdrawals; nor any presumption about their validity. But each will perhaps remind us of a collective stake in the way individual strands are entwined in our sport, and its history.

Hough's personal legacy has long been secure, having nurtured many important horses and horsemen. The latest of these, of course, is GI Breeders' Cup Classic third Global Campaign (Curlin)–whose return to WinStar, where he was bred, circumscribes a two-year comeback for a trainer who picked him out, along with Sagamore president Hunter Rankin, as a yearling.

Without deprecating the opportunities available to those apprenticed to the industrial trainers of today, Rankin prizes the disappearing privilege of a mentor who, in turn, directly represents not just the era of Woody Stephens and Allen Jerkens but also a forgotten generation of hardboots. Hough learned the ropes under one William Tompkins at River Downs, whom he describes as “still the best horseman I've ever been around.”

“There's no better description of Stan Hough than 'old-school',” Rankin says warmly. “He just is the consummate horseman. He knows his horses really well. He loves his horses. Everybody knows about Stan, and everybody respects the way he went about his business: the way he trained horses, the way he interacted with the horsemen.

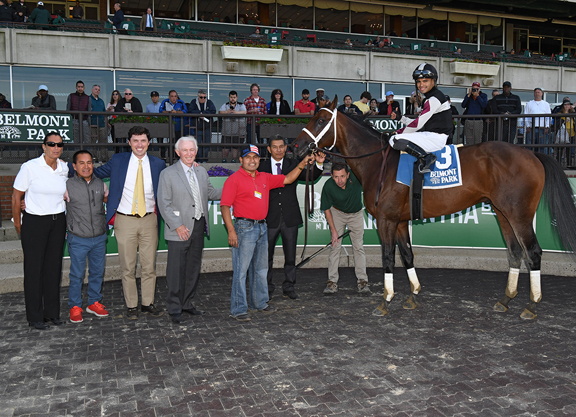

Global Campaign took the Sept. 5 Woodward | Sarah Andrew

“But 'old school' doesn't necessarily mean stuck in his ways. He's really innovative in the way he trains. He works horses from a lot of different poles. He gallops them different every day. He doesn't jog a whole lot. He obsesses over what they're going to do next day–and not just Global Campaign. It's every horse. I would say, 'Stan, you don't need to worry so much about this one, or that one.' He can't help it, you know?

“I think that's the mark of a true horseman. Not that you're right all the time, but just that you'd do anything to make it work. He's a master. Doesn't say a whole lot, doesn't have any interest in being the center of attention. He has always just loved the game.”

Rankin's admiration, moreover, is not confined to the horse lore. Hough has seen a lot of life. He was only 16 when he joined Tompkins; and little older, when becoming a husband and father for the first time.

“Trust me, no matter how great a horseman he is, he's an even better man,” he says. “He's like a second dad. We are borderline inseparable. My dad is the best, but Stan has just been such a gift to me. I can't imagine my life without him, really. You won't find anybody that would say a bad word about him.”

Part of what we are losing, in the retreat of men like this, is the trainer whose “eye” oversees the whole process: not just the conditioning, but the original discovery of potential. If the focus was wrong, when Hough worked the sales or made a claim, he would have to tighten that belt an extra notch. That kind of thing concentrated the mind in a fashion you don't see so often, now that barns are largely stocked by agents and managers and so on.

While Hough did gain one or two powerful patrons, along the way, he started out claiming horses at places like Hazel Park, Detroit. As Rankin says: “For the most part, he did it on his own; and he did it his own way.” In time, he gathered the seedcorn to buy Proud Appeal (Valid Appeal) at the Hialeah 2-year-old sales in 1980, with a partner, for $37,000. True to that old-school grounding, the following year he trained him up to Kentucky Derby favoritism with five stakes wins in 10 weeks, culminating in the GI Blue Grass S. In the meantime, John Gaines and Robert Entenmann gave seven figures for a stake in the horse. Clients similarly profited from his talent, as when Paul Robsham sold Discreet Cat (Forestry) to Godolphin after he won on debut at Saratoga. Or they just banked the purses, as when Half Iced (Hatchet Man) won the 1982 Japan Cup in the Firestone silks, his 16th sophomore start.

But what gives ultimate symmetry to Hough's retirement, aged 72 and after 2,212 winners, is that Calder closed its doors the same day. That was where Hough made his name, and you can't help but feel that its loss should focus our community's attention on what it is prepared to forfeit, what it wishes to preserve, and how. That is not a simple process.

Everyone would agree that the fate of Sagamore, for instance, is the unique prerogative of its owner. Yes, it's gratifying that Hough should have secured for Global Campaign the chance to extend a sire line tracing to the “Gray Ghost” himself, Native Dancer. And we'd all be delighted should someone, someday, decide that the Kevin Plank chapter in Sagamore's Turf history need not be the last. In the meantime, however, everyone accepts that he can do as he wishes with his own property. Presumably the only way to salvage the farm, for Thoroughbreds, would be an offer to purchase sufficient for him to abandon whatever other purposes he may be favoring.

Now it must be said that the same indulgence is seldom extended to the owners of “Gulfstream Park West,” as Calder was unhappily rebranded. They are not in this business as knights in shining armor; not trustees for our community. They are here to get the best possible dividends out of their property for their shareholders. Without a neutral authority to arbitrate a South Florida racing calendar, it's a perfectly coherent accounting decision to decide that competition with Gulfstream isn't sufficiently viable for their purposes.

Few of us have any idea about how things unravelled over the lease that had brought Gulfstream's owners into play for Calder's final years; or, indeed, what the future priorities of that operation may be, for its hugely valuable real estate round the country. In the case of Churchill Downs Inc., however, people know exactly what they are dealing with. And while we may despair over the consequences for Calder or Arlington, then we must at least acknowledge that when they do commit to a track, as a sustainable business proposition, they will do a professional job of making it work. Seeing what they are doing up the road at Turfway, certainly, they seem likely to make Kentucky the sport's center of gravity even as the opposing coasts are bogged down by diverse problems.

Looking around, and looking ahead, you have to ask how vigorous competition is likely to be among track owners. That's a concern, whether or not Churchill themselves prove interested in other historic sites that may become available. If they are, well, we all know that stronger competition would be healthier for the consumer. And if they aren't, then just who is going to step up?

Running a racetrack as a profitable business is not straightforward, especially when so much can hinge on state regulation, slots, etc. E.P. Taylor famously led the consolidation of the sport in Ontario, shutting down the leaky-roof circuit and throwing everything at a state-of-the-art track at Woodbine. That kind of process can be brutal, and there can also be undesirable side-effects. After Calder's closure, for instance, you seriously fear for the surfaces at Gulfstream, most obviously the turf course.

Nonetheless, Taylor's vision and leadership showed the fearlessness required for the grasping of nettles like this.

The fact is that ruthless pursuit of profit can only be thwarted by its removal as a consideration. In Britain, The Jockey Club has surrendered its original function as a governing body and evolved into custodian of such historic racetracks as Newmarket and Epsom, where it also owns the communal training facilities. And Ascot, of course, is owned by the Queen herself–not terribly likely, you would say, to sell up for housing any time soon.

That's not a solution available to Americans, of course, since 1776. But it's no good wringing your hands over the cynical indifference of commercial operators to tradition, or community, or legacy. If enough people of sufficient wealth are sufficiently concerned, perhaps something might yet be done.

The Breeders' Cup, after all, was founded on communal contribution toward the corporate benefit of the industry. It's not as though all racetracks are doomed to lose money. Otherwise Churchill wouldn't be in the game. And if the profits of tracks owned and run by stakeholders were routinely ploughed back, then you could aspire to a virtuous circle: better product, better handle, better gates, better television, better purses.

So, as ever, it comes down to the caliber of people. Let's return to the question asked at the outset, about the fabric of the Turf. Many would suggest that a horseman like Hough is where the answer starts. He guarantees the interests of the horse, whatever it takes. The question is whether the same standards can be met by everyone else involved in getting the show on the road. Because the choice is either to keep blaming other people for neglecting the interests of our sport, or to get together and do a better job ourselves.

The fabric of the business is never more literal than in the bricks and mortar of a racetrack. But those, too, no less than the condition of a horse prepared by Stan Hough, will always reflect the quality of the people responsible.

Remember what Rankin said about Hough. It's not that you're right all the time, just “that you'd do anything to make it work.”

The King of Calder has abdicated, and his kingdom has disappeared. But the wider realm can still be defended, and those who can afford a suit of armor should maybe get together and show some knightly qualities of their own.

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.