By Chris McGrath

Bought yourself a mare in Lexington this week? Good for you. You have kept the faith. In many cases, that will be because you have seen it all before: you've ridden out bumps in the economy, and eked out value from these stoical and enduring creatures by borrowing their impassive engagement with the patient rhythms of Nature. It's a long game, after all, one that will absorb pandemics and presidential cycles like a passing April shower.

But even the longest journey starts with a single step. And many of you will already have had an assignation in mind for your new mare from the moment you first folded down the catalogue page.

As we know, the stallion farms have done their bit to animate a market stricken by anxiety about the current strain on the global economic system. All the big commercial operations have made headline cuts in fees for 2021, and I'm already salivating over some of the value to be identified in our annual winter appraisal of the stallion market.

Some people, however, have muttered their scepticism as to the substance of these gestures. Has there really been a comprehensive remodelling in the base cost of breeding a Thoroughbred? Or have farms merely camouflaged the decline they had invited in overpricing particular types of stallion?

Well, I thought that might be worth investigating. Intake by intake, I've taken a look at the relative decline, between stallions at different stages of their careers, at 12 leading farms in Kentucky. We know, after all, that few sires ever again command a fee as high as their opening one; and that they will generally take repeated trims until either discarded, or achieving something to suggest a long-term viability.

How much deeper than “normal”, then, were the cuts this time round? And where were they concentrated?

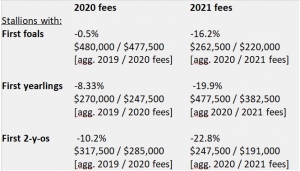

This table charts the decline, in each of the past two years, in the aggregate stud fees charged by sires at the same stage of their careers on these 12 farms.

It's a broad-brush exercise, very soon complicated by stallion traffic in and out of the Bluegrass by the likes of California Chrome (out), Laoban (in) and Daredevil (out and in). But my feeling is that when these farm owners talk about us all being in this together, they could also be addressing their stallions. Because they do, in the round, appear to have led sires young and old out onto the high road to meet the breeders halfway.

If there is divergence in the angle of the knife making these cuts, then it's not so much between stallions at a different stage as between stallions on different farms. And you won't find it hard to decide which were in deadly earnest, and which were pretty much making standard business decisions about individual stallions who would have been in trouble anyway.

Authentic–priced at $75,000–is the most expensive of the 2021 intake of new stallions to date | Breeders' Cup/Eclipse Sportswire

New stallions for 2021 vs. in 2020

I suspect that the one and only group of stallions that are being protected, as a class, will turn out to be those making their entrance to the market. These, presumably, are again guaranteed books of grotesque size; certainly a lot of them appear to have been priced that way.

But there's no point comparing their fees with those who started last spring, as every intake varies in commercial appeal: a $150,000 tag for Justify, for instance, helped to elevate the aggregate fee value of those who started at these 12 farms in 2019 at $480,000, compared with $262,500 for those who began earlier this year. The point here is to compare the relative loss of value suffered, by each intake, at the equivalent point of their careers.

And that's certainly instructive in the case of those who entered stud in 2020, whose first foals will be delivered in the new year. Collectively, the sampled farms send these stallions back to market in 2021 at an aggregate fee cost of $220,000, down 16.2% from the $262,500 they collectively charged in their debut season.

This is a major departure from the way studs have sought to maintain values at least until a first crop of weanlings has entered the ring. In 2020, by contrast, the same farms were able to charge $477,500 for sires entering a second season, virtually unchanged from an opening $480,000.

This time around, even the stars have been repriced–most strikingly at Spendthrift. A mare apiece to Omaha Beach, Vino Rosso and Mitole would have cost a total of $100,000 last spring; now you can get to them all for $75,000.

Sires with first-crop yearlings in 2021

The next group, meanwhile, is now reaching the stage–with their first yearlings about to go into the ring–when commercial breeders typically abscond to the next round of cadets, and books start to erode. This year, sires who entered stud in 2018 were charging $270,000 from $247,500, down 8.3%, with five of 13 taking cuts. But the group who entered stud in 2019 will be charging $382,500 from $477,500, down no less than 19.9% on their last set of fees. Only four of 19 stallions in this group have managed to hold their 2020 fees.

The Factor is an example of a sire whose fee has held | Lee Thomas

Fourth-year (and beyond) stallions

Next we reach a group that tends to cause breeders really to back off, unless their first yearlings have enjoyed a conspicuous market vogue. Because in his fourth year we start to learn whether a stallion's first juveniles can actually run.

The sires who entered stud in 2017 duly eased their 2020 fees by 10.2%, from $317,500 to $285,000, albeit the majority of farms actually held their nerve and their prices. Those who entered stud in 2018, however, will be taking the equivalent step in the new year at $191,000, down fully 22.8% from $247,500.

Hereafter comparisons become harder. This is the crossroads of every stallion's career, with the whims of the market now measurable against results on the track. So you'll have one guy packing his bags for Turkey even as the next turns out to be Constitution, upgraded to $40,000 and now $85,000. In terms of aggregate fees, then, the winners will very often redeem the damage done by the losers. For present purposes, the flux is such that it is more instructive to assess those who come out the other side of this winnowing process.

For instance, the handful still on these farms with three crops of runners (entered stud 2015) are certainly sharing the pain. The bare half-dozen still in business will be charging $67,500 between them in 2021, compared with $85,000 in 2020 and $125,000 the year before.

Consolidation, already so difficult because of the commercial infatuation with unproven sires, is becoming harder and harder. Move on a couple of intakes, to those with a fifth crop of runners (entered stud 2013), and it speaks volumes for The Factor, say, that he can hold even a fee he has already outpunched when a studmate as accomplished as Union Rags must take a cut of no less than 50%.

With exceptions, even stalwarts like Tapit have seen cuts going into 2021 | EquiSport Photos

Benchmark sires

And what of those who set the standard; the happy few who, having established their merit and viability, represent the model for those still trying to make a name for themselves? Operating at all levels of the market, from War Front to plucky achievers like Midshipman, they comprise the solid foundation for the whole stallion industry.

Sure enough, after a long bull run in the bloodstock market, these older sires (a total of 35 across our 12 chosen farms) collectively maintained their covering value in 2020 at $2,280,000, up marginally from $2,225,000 the previous year. For 2021, however, despite the odd hike (Into Mischief, Uncle Mo, Speightstown and Munnings) they have slipped 8.2% to $2,041,500.

That's just about half the percentage loss, then, of those embarking on their second season. Normally, these are the two stable bookends to all the fluctuations in between. But even this lesser erosion implies some exceptional opportunity among the kind of proven sires who can make a mare, who can build a family, pending any return to the mechanical commercial exploitation of unproven sires.

I do see, nowadays, how that kind of thing is primarily driven by breeders; and I no longer blame the farms for loading the books of new stallions when the resulting stock will be given such a brief window of opportunity on the track. At the best of times, farm accountants have a terribly difficult balancing act. And, in reacting to the present crisis, it looks as though that balance extends at least to their collective use of the scythe. Admittedly, you'll find that the cuts may be a little more jagged on some rosters than others. But the overall result is that there is opportunity across the herd.

So if you do insist on using a newcomer, with such luminous value across the rest of the spectrum, then good luck in your incorrigibility. Because if the overall “supply” did need some kind of correction, then so too, unmistakably, does our demand.

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.