By Dan Ross

By the beginning of April, there had been two fatal musculoskeletal injuries during the current Santa Anita meet. Wind the clock back to an identical window in 2019, there had been 22.

During Aqueduct's benighted 2011-2012 Winter meet, 21 horses died, 18 of which were fractures sustained during racing. Over the next seven years, New York's four racetracks saw a 50% reduction in racing fatalities.

What is the common denominator? Huge advances in identifying those horses at higher risk of sustaining fatal injuries in racing and training, and much tighter safety nets to filter these horses out of the racing pipeline before a catastrophic event occurs.

Racing's North Star is to reduce the number of musculoskeletal injuries to a single duck egg. But there remains a stubborn impediment: The ability to easily and accurately identify those emerging and subtle injuries that can't be detected with the naked eye but have the potential to devolve into a sickening fracture.

How prevalent are these sorts of issues? Well, 21 one of the 22 horses that died during Santa Anita's 2018-2019 Winter meet showed pre-existing pathology at the site of their fatal injuries.

Enter stage left the 21st century, and a collision of new technologies that bring an objective, mathematical approach to pin-pointing these hitherto elusive and barely perceptible problems.

The New York Racing Association (NYRA) is deep into a project that began last summer to trial a sophisticated biometric sensor mechanism which fits snugly into the horse's saddle cloth and can detect minute changes in a horse's gait at high speed. Called StrideSAFE, the sensor has been proven to detect problems in a horse's stride sometimes weeks in advance of a catastrophic event occurring.

Over on the opposite side of the country, The Stronach Group, under its 1/ST banner, is gearing up to unveil its own system which uses high-definition cameras to create detailed skeletal movement maps of horses as they navigate the racetrack. Company officials believe the technology has the potential to similarly red-flag horses at the very earliest warning stages.

What's more, these new kids on the block converge with an emerging generation of imaging modalities-think PET, MRI and CT-more capable than their diagnostic ancestors of providing a clear yes or no answer to the presence of subtle pre-existing problems.

And now, some of the industry's most pragmatic, unflappable leaders are making the argument that, given further development and understanding, these biometric systems hold the key to reducing fatal musculoskeletal injuries from the sport even further-potentially altogether.

“This is probably one of the most important contributions to the Thoroughbred horse industry that has ever been made,” said Scott Palmer, equine medical director for the New York State Gaming Commission, about the StrideSAFE sensor. “I do have a big stake in saving horses' lives, and so, in some respects this has been a holy grail.”

The Sensor Is The Ultimate Jockey

When David Lambert studies horse racing through a technology lens, he compares it to a ladder propped against a house going into the third-floor bedroom window.

Currently, racing's hitherto timid embrace of cutting-edge technologies-even basic training monitors, for example, used liberally for decades in human sports-have kept the industry rooted to the lawn.

“Me trying to get this [StrideSAFE sensor] introduced is the first rung of the ladder,” Lambert explained. “Keep that up over time, slowly but surely, you'll get right up to the third floor and walk into the bedroom.”

Lambert is a loquacious and affable 73-year-old veterinarian hailing from the North of England, who has dabbled in the odd bit of race-riding and training. He's lived Stateside for more than 50 years, during which time, he's spent decades digging through the mathematical arcana of performance prediction, and the role that sensors play.

Mickael Holmstroem, a Swedish PhD with expertise in equine conformation and locomotion, and Kevin Donoghue, professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Kentucky, have been Lambert's business and academic partners for much of this journey.

In 2019, they all formally embarked upon a mission to design a system that StrideSAFE looks like today. In all, Lambert reckons he has poured $1 million of his own money into its development.

It's no surprise, then, that he talks about it with the enthusiasm of a teenager with the keys to his first car.

“The sensor is the ultimate jockey,” Lambert said. “It's the best rider that ever rode a horse, never forgets anything, and picks up data 800 times a second in each of three directions for a total of 2,400 data points a second from the horse.”

So, how does it work?

This wireless iPhone-shaped device fits snugly into the saddle towel, and eight-hundred times a second, it takes an assortment of measurements to capture in minute detail the movement of the horse at high speed.

These measurements include the horse's acceleration and deceleration, its up and down concussive movement, and its medial-lateral motion-in other words, the horse's movement from side to side.

Ultimately, the sensors capture the sorts of high-speed lameness invisible to the naked eye but significant enough to cause major musculoskeletal failures at some point down the line unless someone intervenes on the horse's behalf.

“A horse can basically stand to race. Their bones are strong enough, their ligaments are strong enough,” said Lambert. “But what they can't stand is imperfection over and over and over again. They're going to break something.”

When explaining the equine biomechanics underpinning the success of the StrideSAFE technology, Lambert first compares the horse to an antipodean cousin-the kangaroo.

“People don't get that,” he said, of the comparison. “Sixty or seventy percent of the energy it produces to go fast is from spring or elastic recoil.” He then breaks a single stride into three stages.

In the first phase of the gallop, the hindlimbs load and propel the horse forward, kangaroo-like. In the second, the horse shifts its weight to the front, its forelimbs acting like shock-absorbers. This is followed by a period of suspension, the horse entirely airborne, a time for it to catch its breath.

But if the horse suffers a physical problem, however, it cannot adjust its body to compensate when its feet are on the ground. It can only do this midair, rotating its spine and pelvis in preparation for landing.

“The horse does all kinds of things in the air, twisting and shaking and moving,” Lambert explained. Imagine a race-car hurtling along at high speed, one of its bolts working loose.

What's more, these midair adjustments are infinitesimal, occurring within a 1/100th of a second window imperceptible to even the jockey-but not a sensor.

“It tries its best to re-align itself and repeats it all over again,” Lambert added, of the horse. “Then six, eight, ten weeks in, that front leg is going to feel it. You're going to get a joint or a knee. You start to see the obvious lameness.”

StrideSAFE works like a traffic light signal, providing a green for all-clear, a yellow for caution, and a red for possible danger. In mathematical terms, a red means that the horse's gait abnormalities are beyond two standard deviations of the norm.

It's important to note that a red-light doesn't necessarily indicate a brewing issue. It could simply mean the horse is slow or that it doesn't try.

Nevertheless, from trials at tracks in Tasmania, and at Emerald Downs and Kentucky Downs here in the U.S., the sensor has repeatedly proven effective at highlighting gait abnormalities sometimes weeks in advance of a fatal breakdown.

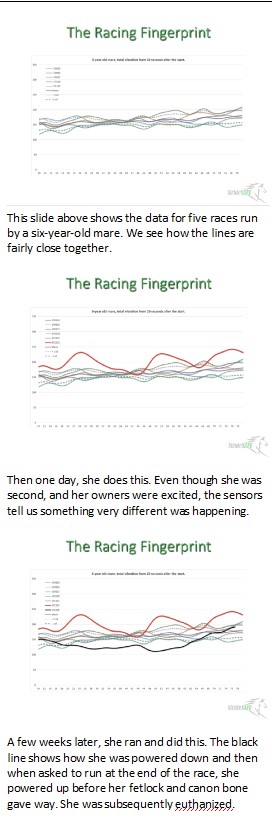

Lambert shared data slides showing the five-race progression of a 6-year-old mare. During her first three runs, the mare's way of going-what Lambert calls her “fingerprint”-showed no abnormalities.

Her fourth race garnered a red-flag, however, despite finishing an encouraging second that delighted connections. A few weeks later in her fifth race, the mare fatally broke-down.

“In a normal day of racing just one or two horses will get a red flag warning and this small group contains a significant proportion of the horses in danger of catastrophic injury,” Lambert said.

Early injury detection can help to not only avoid painful, expensive and time-consuming treatments but expedite convalescence time, too-a fillip for an industry grappling with the consequences of a dwindling horse inventory.

“Attrition of racehorses is an enormous problem,” said Scott Palmer. “This device gives the opportunity not just to identify horses with a gait abnormality before it becomes evident normally to a human being, it allows regulatory veterinarians and racing officials to work together with trainers early in the process to help keep horses in training.”

Last summer, NYRA used StrideSAFE on every horse in one race per day at Saratoga, allotting each the requisite red, yellow or green label. By the end of the meet, 3% of the horses measured had been red-flagged.

All participants were then tracked over the subsequent four months, to see if and when they returned to race-day competition.

Of the green horses, 78% were able to race back within four months. Of the yellow horses, 72% raced within four months. But only 40% of the red-flagged horses returned to race within four months.

“If you have horses that don't run back regularly, don't race on a regular basis, there can be a number of reasons for that, but the most common one is lameness,” said Palmer.

So impressed has Palmer been with the technology, NYRA has used it on every horse to race during the most recent Belmont Park and Aqueduct meets, for a number totaling roughly 6,000 recordings.

That data is now being evaluated. Plans are also afoot to trial the technology on horses during training. But Palmer already imagines a future where this technology is a more permanent part of the NYRA furniture.

“My vision about this is that when I get notified of a red-alert, I can just send an email to the trainer that says, 'trainer, your horse just got a red-alert today. What does it mean, what does it not mean, and what are your next steps,'” said Palmer. “That horse is going to get extra scrutiny, and that's the name of the game right now.”

And it reveals much when Palmer, chief veterinarian at one of global racing's highest profile jurisdictions, admits that StrideSAFE has evolved his understanding of the equine athlete.

He said, “I will never look at the horses in the same way.”

While StrideSAFE utilizes motion sensors that attach to the horse, 1/ST is readying for later this year the launch of a three-year, multi-million-dollar effort to design a biometric system with multiple uses, including the ability to create detailed skeletal movement maps of horses using high-definition cameras.

“We're at the beginning of the journey in terms of 'how far can we take it?'” said Paul Williams, who heads up technology at 1/ST. “But we're beyond the beginning of 'very excited about what it can do.'”

The basic building blocks of this system consisted of creating virtual 3D models of each 1/ST track which were then then mapped against the position, angle and zoom of the TV cameras already dotted around these facilities.

It took a year, said Williams, to be able to pin-point a horse on the track to within 13 centimeters of its actual location. Since then, he and his crew have whittled that down to a six or seven-centimeter range of accuracy.

“That gives us a level of accuracy where we can track the physical horses and people and vehicles and weather, weirdly, of the locations from the TV camera,” said Williams.

And with 85 million historical race clips already plugged into the system, “that's a nice place to be because you have such a large data lake to start to test and to infer theories,” he said.

Among the information the system collects includes acceleration and deceleration and horse stride length. What's more, the system, said Williams, can “effectively replace” and in some instances vastly improve upon a host of commonly used industry practices and technologies, like start-stop time, race order, race-speed, top-speed, and the number of times the jockey uses the whip.

“Even down to pseudo-jockey aero dynamics, based on where they're positioning their weight on the equine athlete,” Williams said, pointing out that some of the derivative data could be packaged and geared towards gamblers.

And from this model, Williams and Dionne Benson, 1/ST's chief veterinary officer, are in the process of adapting it to identify patterns of horse lameness not visible to the naked eye.

And from this model, Williams and Dionne Benson, 1/ST's chief veterinary officer, are in the process of adapting it to identify patterns of horse lameness not visible to the naked eye.

The basic principle is fairly simple: High-definition TV cameras will pick up QR codes-think restaurant menu barcodes-attached to a horse's saddle towel during training, sending back in real-time a rich pool of highly detailed, high frame-rate data.

Over time, this system can accrue historical skeletal movement maps for each horse at all gaits, from walk to high-speed workouts.

Though this part of the system is still being beta-tested, the range of motion captured by the cameras is so sensitive, said Benson, they can pick up fractional changes to the fetlock, for example.

“At the trot, fetlock drop is very informative,” Benson explained. “If we know a fetlock is dropping more than it had been, that is a potential indicator of a problem going on-maybe because the ligament is weakening.”

A key to accurately pin-pointing horses with early brewing problems is a matter of proportion-in other words, having a comprehensive enough database of races, workouts and training days for the computer algorithm to identify outliers.

An outlier could be a horse that displays troubling gait changes over a period, for example. Or the system could red-flag certain horses using proven patterns of movement abnormality among horses in general. And so, there's another crucial component to this venture.

“Right now, you can't see a lot of the stuff that's picked up by the computer with the naked eye. So, there's going to be a period of time where we're going to be looking at issues that we may think is something but isn't,” said Benson.

The system's ultimate success, therefore, also rests upon what protocols are in place to siphon red-flagged horses towards diagnostic technologies-modalities like the PET and MRI units already housed at Santa Anita-capable of detecting those minor bone adaptations that can turn ugly.

Given the system's performance to date, both Williams and Benson appear noticeably sanguine about its promise to screen out early the horses who illustrate the sorts of subtle problems that could prove catastrophic.

“I'm pretty confident, because of the quality of data that keeps coming out of this thing, that we will get very close,” said Williams.

The system is expected to be launched and live at all 1/ST locations later this year, including training locations.

“If we get positive feedback there, I think we'll look to extending it beyond our tracks to our partners,” said Williams. “Horse populations move around the country, and to have this be a useful benefit for the industry, it's got to track a horse all the time.”

What stands out from discussions with proponents of these biometric technologies is the potential for adaptation, using them to compare the relative strengths and weaknesses of different jockeys, for example, a horse's performance on different tracks, and how hard it works.

Lambert tells the story of a horse fatally injured during a race. He said the post-race read-out showed noticeable gait abnormalities a full 70 seconds before the fatal event-from the minute the horse exited the gate, in fact.

And so, theoretically, such systems could also eventually be used in real-time, opening the door to preventing catastrophic injuries from occurring during a race or workout.

For the ambitious trainer looking for an edge other than through pharmaceutical intervention, therefore, technologies like StrideSAFE hold the key, said Lambert.

“You get to know your horse really, really well. You get to be the best horseman you can be by having the right kind of data to care for your horse,” he said. “It's the future.”

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.