By T. D. Thornton

The concept of perception versus reality has been a core plank on both sides of the highly publicized “detrimental conduct” case ever since the New York Racing Association (NYRA) first tried to banish trainer Bob Baffert eight months ago. On Tuesday, the second day of a hearing process that could lead to Baffert's exclusion from New York's premier tracks, the murky interpretation of who should be considered the true victim and which entity is in need of protection from harm rose to the forefront in the form of arguments over “social licensing” that at times played out in tense and pointed fashion.

Although Baffert is the most easily identifiable Thoroughbred trainer in North America, the key witness who testified Jan. 25 was not at all a recognizable name within the sport. Some 7 1/2 hours of testimony and cross-examination from four witnesses were anchored by about 90 minutes of debate regarding the opinions and PhD expertise of Dr. Camie Heleski, a University of Kentucky equine sciences professor who specializes in what the general public thinks of as horse racing.

“If somebody carries a lot of weight, if they have a strong visual branding in a certain piece of the industry, that's going to be noticed by a larger group of the public, a larger group of, let's say, horse racing fans than if it was not such a memorable person,” Heleski testified. She later added that, “Anybody that's paying attention to racing is going to know who Bob Baffert is.”

Heleski explained that in general, the public tends to regard any highly publicized news about pharmaceuticals in horse racing as something that could be damaging to the sport's social licensing, which is a way of terming general acceptance.

“Most of the time, they're simply feeling if there was a drug or a medication violation noted, they feel like it's bad. They kind of put it all under the umbrella of doping,” Heleski said.

And when Kelly McNamee, a lawyer representing NYRA, asked her to tie in the public's collective thought process and how it relates to Baffert's history of equine drug positives, his trainee Medina Spirit's betamethasone overage when winning the 2021 GI Kentucky Derby, and the “over 70 horses that have died under the care of Mr. Baffert,” Heleski didn't hesitate to answer that all of those things combined could adversely affect racing's social license to operate.

“I think drug and medication [positives] from a very prominent person carry more weight than people that are not followed as closely…” Heleski said. “[And] if a trainer has a large number of deaths in their stables, that's going to be looked on poorly.”

But under stern cross-examination from Baffert's lead lawyer, W. Craig Robertson III, the University of Kentucky professor at times seemed overwhelmed when challenged to explain how it could be Baffert's fault that the general public doesn't understand the difference between therapeutic medications and doping.

Robertson also hammered home points about Baffert's history of awards for sportsmanship and good deeds within the industry, plus his well-documented contributions to aftercare. He wanted Heleski to explain how, if Baffert is such an allegedly detrimental presence who could hurt NYRA, why didn't any activists protest his presence at Saratoga last summer, and why did the track enjoy record betting handles at that meet despite Baffert trainees being in the entries?

Robertson also attempted to dismantle Heleski's “amorphous” concept of social licensing, which, she admitted, has nothing to do with an actual “license” that a person or entity could apply for based on regulated standards, like a racing license.

But assuming such a concept exists, Robertson asked Heleski if it wasn't also part of NYRA's obligation to treat all trainers fairly as part of that social license to operate.

“They should treat trainers fairly, yes,” Heleski agreed.

And if NYRA singled out one trainer–like Baffert–for allegedly unfair punishment, Robertson wanted her opinion on whether “the public might not like that, either. That could hurt a social license to operate, couldn't it?” Robertson queried.

NYRA's legal team objected to that line of questioning, and hearing officer O. Peter Sherwood wouldn't allow Heleski to answer the question.

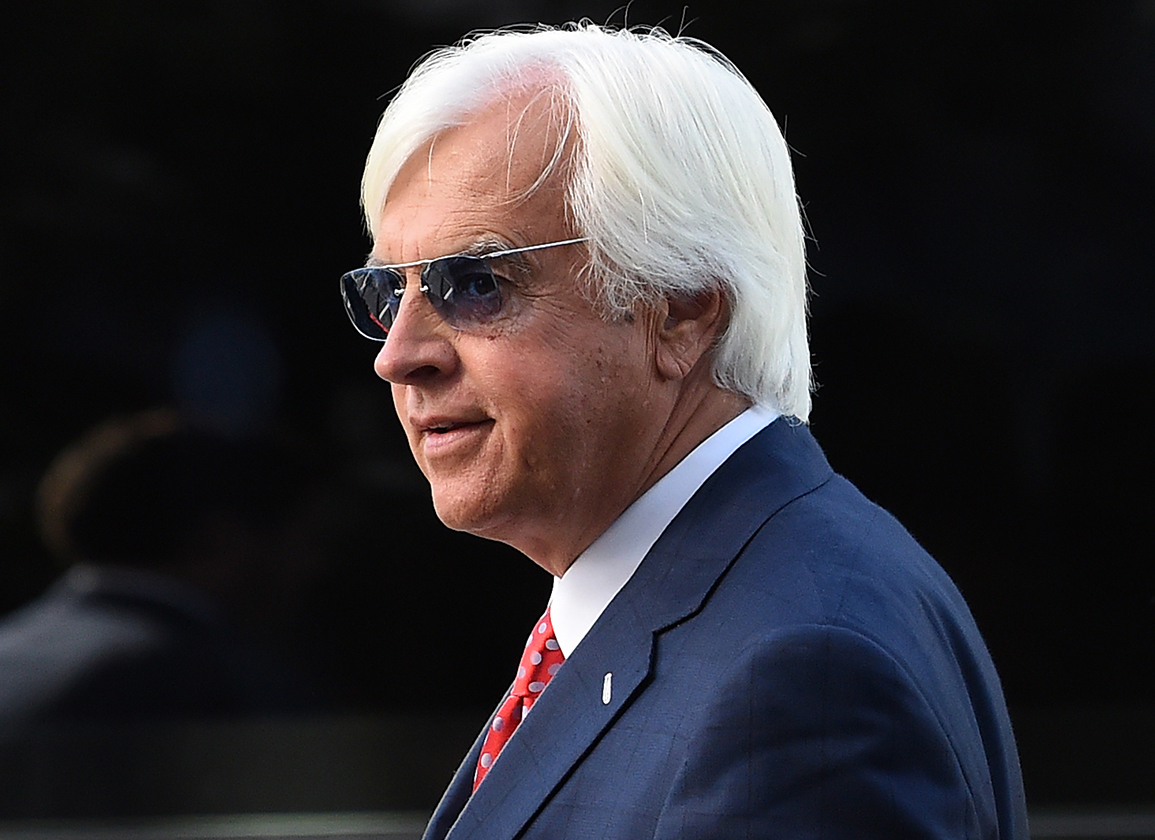

Baffert himself was not called upon to speak during the day-long proceedings in New York City. On the Zoom webcast made available by NYRA to the media, the Hall-of-Fame trainer could occasionally be glimpsed sitting alongside his lawyers in a conference room, dressed in a dark sport coat and open-collared white shirt.

Although his facial expressions were hidden behind a mask for pandemic precautions, Baffert's posture suggested tedium more than anxiety. He generally kept his hands folded in front of him, sometimes absently working his thumbs together repetitively while occasionally reaching up to flick his thick, silver-white hair off his forehead. For the most part, he looked more like a gent waiting for a bus than a seven-time Derby-winning trainer waiting to find out if he'd be exiled from one of America's most prominent racing circuits.

In previous legal pleadings that failed to keep Baffert's hearing from happening at all, his attorneys have described these proceedings as a “fait accompli.” Yet despite the fact that NYRA came up with the newly invented process for holding the hearings, the list of charges against Baffert, and was responsible for selecting the hearing officer who will decide Baffert's fate, a federal judge ruled last week that NYRA has a right to move ahead in that manner.

NYRA had outright banished Baffert May 17, 2021, in the wake of Medina Spirit's still-not-adjudicated Derby drug positive, noting that four other Baffert trainees had tested positive for medication overages in roughly the year before that. On July 14, a federal judge granted Baffert a preliminary injunction that allowed him to race at Saratoga, Belmont and Aqueduct. That injunction has since been made permanent, but with the legal stipulation that NYRA must afford Baffert a hearing process before deciding whether to kick him out or not.

NYRA is charging that Baffert's alleged conduct is or has been “detrimental” to three entities: 1) The best interests of racing; 2) The health and safety of horses and jockeys; 3) NYRA business operations.

Dr. Pierre-Louis Toutain, a France-based veterinarian considered an expert in pharmacology and toxicology, testified earlier Tuesday for 1 3/4 hours.

Some of Toutain's testimony tended to drag, in part because he was asked to offer definitions of and uses for phenylbutazone, lidocaine and betamethasone, three of the substances that NYRA purports are related to Baffert's alleged wrongdoing. Toutain also good-naturedly apologized a number of times for English not being his first language as he testified remotely while on a six-hour European time difference.

Toutain provided one of the lighter moments of the day when he politely interrupted a drug question from one of Baffert's attorneys, Clark Brewster, to ask, “Are you a scientist or a lawyer?”

When Brewster replied that he was a lawyer, that cued Toutain to know he shouldn't give too technical an answer,

“Ah, so I have to explain simply–okay!”

General laughter broke some of the inherent tension.

But there was no hint of humor from anyone in the room when a NYRA attorney, Hank Greenberg, asked Toutain if the presence of 21 picograms of betamethasone in Medina Spirit's post-Derby blood would have had the capacity to affect his performance.

“Yes, definitively,” Toutain replied.

But Toutain had been talking strictly about an intra-articular injection of betamethasone, which he said was the prevailing way that drug is administered to horses. So when it was Brewster's turn to cross-examine Toutain, he made sure to ask about betamethasone contained within a topical salve or ointment for a skin rash, which is how Baffert has alleged that the betamethasone found its way into Medina Spirit.

“Topical? I am not sure they use it [that way],” Toutain answered.

Toutain then seemed to be confused about whether Brewster was asking if betamethasone was sometimes administered via patch, like lidocaine (which the attorney was not asking).

Brewster then quickly ended his cross-examination of Toutain.

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.