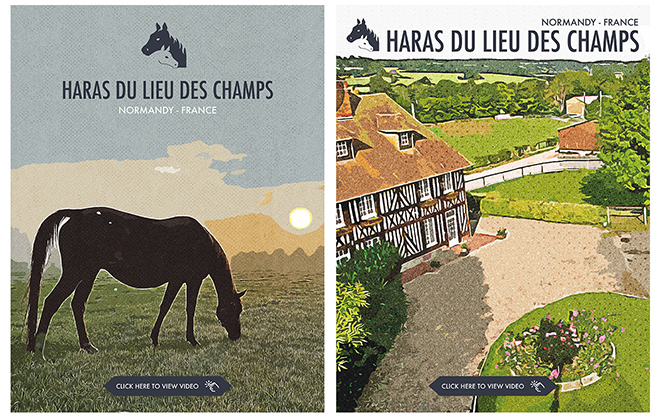

At a time when travel and nostalgia have become poignantly conflated, there is something especially striking about the way Richard Powell is seeking to promote his Normandy farm overseas. You may have noticed a series of pastel evocations in TDN, in the mold of those vintage posters that prompted generations past to book a steamer cabin across the pond. The images are allowed to speak for themselves, accompanied by no more than a video link. Click that, however, and you see that no artifice is necessary to present Haras du Lieu des Champs as an Old World enclave: literally a place in the fields, its 222 green and shady acres innocent of all modern disfigurement.

Like everyone, Powell hopes that it will become easier to board a plane in the months ahead; few, however, can have a more innate sense of the vitalities suspended by the incarceration of our entire species. For Powell himself represents a highly cosmopolitan package: French-American by breeding, he was privileged to receive an apprenticeship at every point of the Turf compass. His time in the United States included stints with Neil Drysdale, Walmac and Denali, and he has a brother and half-brother respectively training on either coast in Leonard Powell and Arnaud Delacour. And, knowing this market so well, he feels that now is the perfect time to offer his farm-a full-service facility embracing breeding, sales preparation and consignment-as a bridge to transatlantic opportunity.

He predicts growing business opportunities for American investors in France, and we'll address those shortly. But he feels these can dovetail uniquely with the ambient fascination of Normandy: from its gastronomy to the D-Day beaches and cemeteries, such a critical conjunction between its own long history and that of the New World. After all, it is only in being deprived of the stimulations of travel and cultural exchange that we have learned not to take them for granted.

Powell has a number of American clients already, albeit they have lately been denied the kind of benefits incidental to their primary purpose as investors.

“It has been sad for everyone,” Powell says. “But the world has to move forward. Remember the Jamiroquai album, Travelling Without Moving. Even if we can't move, we can still travel in our minds: like when we watch a documentary in the evening, about somewhere on the other side of the world. So we did these illustrations just in a spirit of sharing with people everywhere what we have here-because we know how very fortunate we are, to have it for ourselves.”

Powell credits the inspiration to his wife, Hélène. She reasoned that many people–themselves included–like to hang up these old posters, maybe advertising spas or seaside resorts: Bath or Brighton, in England; San Sebastian in Spain; or, just up the road, Deauville itself. So this could be something that was familiar, as a genre, while also being novel.

Powell credits the inspiration to his wife, Hélène. She reasoned that many people–themselves included–like to hang up these old posters, maybe advertising spas or seaside resorts: Bath or Brighton, in England; San Sebastian in Spain; or, just up the road, Deauville itself. So this could be something that was familiar, as a genre, while also being novel.

“Some of these big studs are investing millions in marketing every year, which of course people like us cannot afford,” Powell explains. “But you can be a precursor, try things before anyone has thought of them. This was something different. The idea was not to tell too much, really to do no more than catch the eye with a proper image of what we have here, with our typical, half-timbered buildings. The atmosphere is just beautiful, when it's sunny and even when it's raining. When you breed in Normandy, there is a whole lifestyle. The sea is next door. Paris is two hours away. As our clients often tell us, we live in a little paradise. I have traveled a great deal, but when I decided to come back to my home region, it was not just because I happen to be from here. It was about l'art de vivre.”

But his transatlantic pitch it is not confined merely to Calvados and langoustines, cathedrals and boutiques. Powell also urges overseas prospectors that the odds here, in terms of the business, are moving in their favor. That applies not just to American breeders, seeking to access European turf quality, but also to British and Irish breeders needing a third way between the Galileo dynasty and all those cheap commercial sprinters. Because stallion options in France, even since Powell bought the farm from his father in 2013, have been explosively transformed.

“You can see from the results how French-breds are excelling all over the world,” Powell says. “Australia, Japan, England and Ireland, the United States, everywhere. Unfortunately this year, after Brexit, we've had quite a few cancellations of mares who were coming over. But we're so lucky that we are 2 km from the Aga Khan Studs, so Siyouni (Fr) is just next door. The French industry has changed so impressively in the last 10 years. The faces are much younger. And all the French farms have been like a team. We all want to go forward, we're buying mares abroad, trying to put France at the center of racing's world map.”

And Powell believes that this momentum is bound to be sustained by growing awareness, in the U.S., of welfare issues. Not only have local bloodlines been rigorously policed, in terms of medication; they also cater to a U.S. turf program expanding in value and prestige. Even within Europe, moreover, the force is with France: Powell predicts that more and more British owners–and, indeed, trainers–will be crossing the Channel to exploit French premiums.

And Powell believes that this momentum is bound to be sustained by growing awareness, in the U.S., of welfare issues. Not only have local bloodlines been rigorously policed, in terms of medication; they also cater to a U.S. turf program expanding in value and prestige. Even within Europe, moreover, the force is with France: Powell predicts that more and more British owners–and, indeed, trainers–will be crossing the Channel to exploit French premiums.

As it happens, some of the farm's most celebrated graduates, have already carried American silks: those of Magalen O. Bryant, associated with some of the most accomplished French steeplechasers of recent times. (They have also gained distinction on the Flat, of course, through the likes of GI Travers S. winner V.E. Day {English Channel}.)

“We've been working for a long time with Mrs. Bryant,” Powell says. “And some of the horses she has bred have been named after great French people who came to the States, like Lafayette (Fr) (Kapgarde {Fr}). We've also been lucky here to breed horses that have run very well in the States, for instance [British Group winner] Dr Simpson (Fr) (Dandy Man (Ire) who ran fifth in the [GI] Breeder's Cup Juvenile Turf a couple of years ago.”

But the defining American connection, of course, remains Powell's father David–who bought the farm in 1980, the year of Powell's birth, after emigrating to France in the early 1970s. The dynasty of horsemen he started here, as already noted, extends its footprint far beyond this farm, not just to the American racetrack but to Arqana, where another son, Freddy, is executive director.

Having made such an impact on the whole industry, his father has naturally been a profound influence on Powell himself. “Always to give your best,” Powell says, asked to condense that influence. “And always to search for solutions, to find answers. Even today, I still have questions for him–and he gives me, I wouldn't say the pleasure but the 'envie' to seek the right thing for the right horse. Because you have to work on them all individually, to find the right balance for each one.”

Powell recalls each of the brothers already mapping out his future with their Lego presents at Christmas: one would devise a miniature auction ring, another a track, and he made a farm. “Right from the start,” Powell says. “No hesitation. I mean, I did work for some trainers when I was younger and lighter, because I love riding. But I always knew that, in the end, my aim in my life was to be a breeder.”

Powell absorbed the examples of great commercial breeders, like John Gaines and Robert Sangster, and towering French horsemen such as Alec Head and Jean-Pierre Dubois. “But besides learning from what others have done in the past, I try to do things my own way as well,” he adds. “That's why it's so important to search for answers yourself, to have your own ideas. You can't just follow older fashion. Because there's no perfect system. The one you make for yourself will combine your own learning environment and what they horses tell you, because they speak for themselves as well.”

Looking at his siblings, and the air of destiny governing their lives, Powell has an obvious context in which to ponder the purpose and scope of our interventions in the development of young horses. Pedigree, he says, will determine the discipline in which a horse can find fulfilment; your job is to facilitate its genetic potential.

“If you have two children, and one wants to be a lawyer and the other a doctor, you're not going to feed them differently,” he reasons. “And it's always better to be the best baker than the worst doctor. So you just feed them as well as you can, do your best until they leave, and then you just have to hope they have a good teacher when they go to uni. If they win, you can only take credit because you didn't mess up that horse when it was in your hands. There's such a long chain, from the breeder to the trainer to the jockey in the race, so it's always teamwork. But when you're breeding, every year brings new questions and you are always just trying to find the potential in every horse. Whether it turns out to be a claimer or a Group horse, National Hunt or Flat, you want breed a winner.”

Powell makes one remark, in what is after all his second language, that captures the enigma of his calling in strangely apt fashion. In breeding, he says, “there's nothing to understand sometimes.” It's an instructive expression, and the corollary is that everyone has a chance. If that were not the case, indeed, Powell says he would do something else for a living.

As it is, the unpredictability of the Thoroughbred makes it legitimate to dream big for every foal. Most horses, by definition, won't grow up to be champions. But that's why there is no excuse for neglecting any opportunity to make the process rewarding in other ways. Hence Powell's zeal to share an environment that not only opens new horizons for breeders, but also happens to be quite charming.

“When all this is over, and people can travel again, I want them to call and say, 'Hey, we loved those illustrations, can we just come and visit?'” he says. “It's always a pleasure to have people here. People come with their grandchildren, they see the fountains and sheep and goats, they can give the horses carrots, they can share our passion. Because what we do, it's all about the dream. You can have a Frankel out of a Group mare and it can turn out to be a donkey. But it happens the other way round, as well. And that's why you keep the faith, why you always tell yourself you can breed a good horse if you put your heart into it.”

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.