By Dan Ross

For nearly three years, a frayed cardboard box has hidden in the corner of a small apartment in the Westside of Los Angeles, buried from view by wooly blankets, a tennis racket with broken strings, worn clothes long earmarked for the thrift store and an old jacket with a broken zipper and patched leather sleeves.

The box is filled mostly with creaky photo albums stuffed full of old newspaper clippings pasted onto faded paper, laminated win pictures–the plastic as brittle as sheet-ice–and handwritten letters. There are magazines and an old DVD and family photographs taken when Kodak shops weren't just a punchline for Millennials.

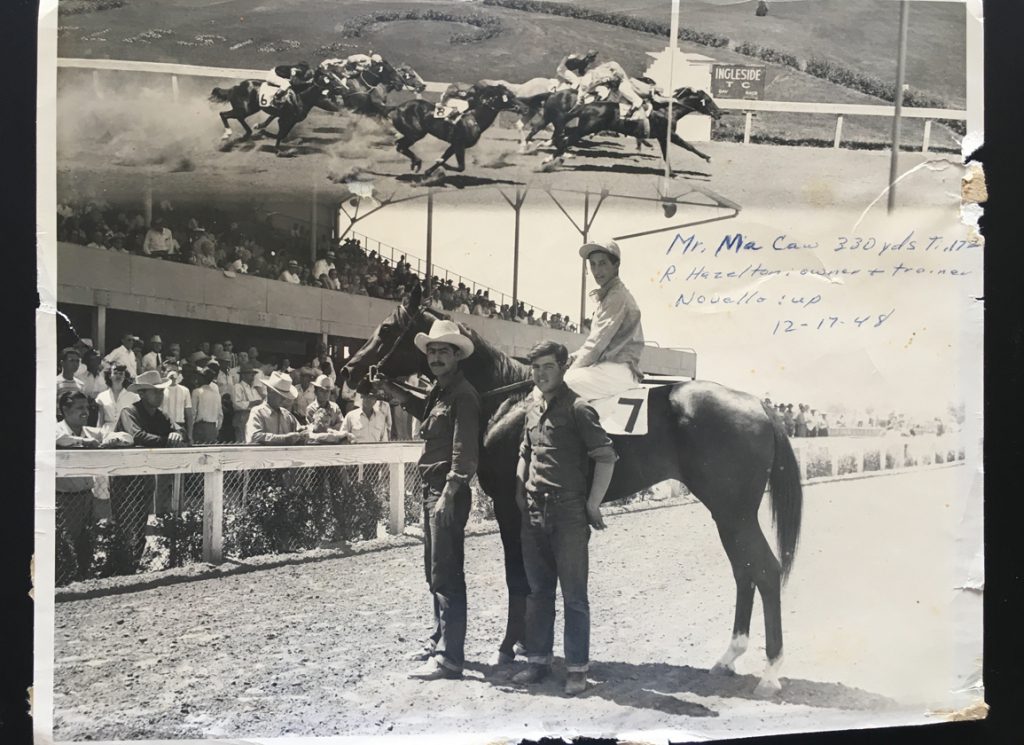

The box has remained undisturbed for years–since its subject, trainer Richard Pierce Hazelton, passed away–only to be unearthed during a spring clean, quite by chance, near the anniversary of his passing in 2019 when he was 88.

“King Richard” lies 10th on America's all-time winning-most trainer list, 4,745 victories officially to his name. Between Hawthorne, Arlington and Sportsman's Park alone, he held 36 individual training titles. For those counting, add another 15 from Turf Paradise.

But like many such boxes–dusty treasure troves stuffed into corner or closet and brought out only occasionally–its narrow scope, a few scattered years among decades, holds something of a frustrating paradox.

While offering up much so more than just its contents, the box still feels an unsatisfying relic, the memories hidden within telling only fragments, leaving one to wonder at what else has already slipped entirely away.

“If Hazelton trains 'em… he's a runner…”

On May 21, 1971, Ellyn Shaunahoff sat down to what one imagines was a desk overlooking a pretty primrose garden and put pen to paper–in florid cursive baby-blue ballpoint–to ask Hazelton for any information on Maxwell G., then a prolific winner in less than prolific contests.

Maxwell G. had been Shaunahoff's favorite horse since attending her first race meet at Hollywood Park on April 19, 1969.

“I have followed him ever since and have cheered his stretch runs many a time,” she writes. “I've been to Del Mar, Santa Anita and even Turf Paradise to see him race.”

At that point in time, Ellyn assumed the then-10-year-old had retired, saying he had “about reached the age limit for racing.” As it turned out, Shaunahoff was a little premature in relegating the old veteran to pipe and slipper.

“There must be a fountain of youth hidden somewhere in Chicago,” wrote the Illinois scribe, Neil Milbert, about the 11-year-old, who had just scored his third victory in a row at Arlington Park just one year later. Even then, AARP was forced to hold fire on sending their magazine to the horse fans called “Maxie.”

Indeed, it wasn't until five years later, in 1977, that Maxwell G. ran his last race when the “grizzled gelding,” as one writer put it, was but a supple 16-year-old.

“Grizzled” really doesn't do the horse justice. A picture from 1972 shows Maxie–tall, raw-boned, yet handsome in elder statesman fashion–standing serenely beside his groom, large ears pinned forward as though gathering radio signals.

By the time of his swan song, Maxwell G. had won 47 out of a staggering 233 career starts, not all for Hazelton, who had claimed him for $1,000 at Yakima Meadows, in Washington, in May of 1965 (another story has it that Hazelton claimed him for $6,200 in 1968 at the Los Angeles County Fair).

It was Hazelton's touch, however, that gave this lowly claimer the veneer of a celluloid star.

The Chicago Sun-Times claimed that Maxwell G., at the height of his fame, brought thousands of fans to the track, lured by his Houdini-like theatrics, when he would race far off the pace before making “a bold bid to win,” as one writer prosaically put it.

Another scribe describes this last gasp maneuver with a tad more relish: “Typically, he will start a race slowly, plodding along behind the field until about the quarter-mile from the finish. Then he will swing wide and make a mad dash for the wire.”

By the time Hazelton had turned 80, memories of his own life were hazy or as terse as Hemingway's prose.

“My dad was involved in horse racing,” he told the poor writer of a Hawthorne Racecourse program, one obviously hoping for Horatio Alger. “I went to live with him when I was seven or eight years old. He had horses. I started galloping them and then I started riding them when I was 14.”

Not exactly edge of the seat stuff.

Hazelton's stint as an apprentice rider can hardly be deemed a bust, not when, south of the border, fans referred to him as “El Ricardo.” But here's his own take on that brief spell, 65 years later.

“I first rode in Phoenix. That's where I was born and raised. I was the leading rider at Caliente in Mexico in 1945. I went to work for the Klein Cattle Company after my stint as a jockey.”

When it came to his horses, however, Hazelton's mind suddenly illuminated, as though a bolt of lightning had passed through it.

“I lost him three or four times but I always claimed him back,” Hazelton remembered, of Maxwell G. “He was a favorite of announcer Phil Georgeff. I remember they took him to the paddock in front of the grandstand and gave him two bushel baskets full of apples. They even named a race for him at Sportsman's and ran it for a few years.”

Hazelton added, proudly: “He was the only horse that was ever on the front page of the Wall Street Journal.”

The 1974 front page Wall Street Journal story in question wouldn't pass editorial muster by today's standards.

“If ever a racehorse was a candidate for the glue factory, it was Maxwell G.,” the story begins, in Dickensian fashion, explaining how poor Maxie, at the age of five, suffered a badly injured left foot, snagged in barbed wire while out punching cattle.

Hazelton would manage the problem appendage with a special shoe that eased the pressure on it. Maxwell G. would repay this favor through what's described in the Journal as “calm affection” and a willingness to “nuzzle strangers.”

As Hazelton put it, “He wouldn't give a nickel for an earthquake.”

Stable hands, the Journal notes, adored the horse.

“When another owner bought Maxwell G. in a claiming race two years ago, one stable hand came to Mr. Hazelton in tears, threatening to quit if he didn't buy back Maxwell G.,” writes the Journal. Hazelton did what was demanded of him.

“What's really amazing is that he's done it the hard way, a nickel and dime at a time,” Hazelton said of the horse's career–an assessment seemingly apropos of the trainer himself and so many of his trainees.

Take Full Pocket, a horse a Sportsman's Park program writer described as one of the “finest” Hazelton ever trained. He was certainly one of the nation's finest and fastest handicap sprinters during that era. In 1973, he won more than $200,000 and was second in the Eclipse Award balloting to champion Shecky Greene for Sprinter of the Year.

Special mention goes to Full Pocket's 3-year-old “reign of terror at Sportsman's.”

This included the “dandy young star's” imperious victory in the $38,400 National Jockey Club Handicap, before a Labor Day crowd of nearly 24,000, when he led home stablemate Moonsplash for “Cowboy Richard,” as one contemporary reporter coined the trainer.

Postage stamp Full Pocket was hardly a Colossus of Rhodes, “something breeders will hold against him,” one miser once noted. But that didn't stop breeders from trying anyway.

By the time the horse retired to stud at Hurstland Farm, in Kentucky–a good outcross to mares with Nearco blood, noted the 1974 Stallion Directory and Farm Register–Full Pocket had won 27 of his 47 lifetime starts and placed in 14 others. He also won 17 stakes and was placed in 11 more.

Again, Hazelton's 80-year-old mind came alive at the horse's memory. “He was one of the reasons I came to Chicago,” said the native of Arizona. “I brought him from the yearling sale for Mr. Bensinger, of the Brunswick Corporation. He named all of his horses. We paid $18,000. That was a lot of money back then. He was never a great sire, but he certainly was a runner.”

Dates and details, places and people–the box is something of a scramble of puzzle pieces sharing oftentimes conflicting information, giving the trainer a shape-shifting quality that somehow only sweetens the myth.

Part of the reason appears to be the man's aversion to the press. As one scribe put it, “I tried to interview him for years but Mr. Hazelton didn't like to talk about himself–or to me.”

One such seemingly slippery fact surrounds his age.

“Jockey records in 1945 list him as having been born in 1929,” wrote longtime Sportsman's Park fixture Don Grisham, of Hazelton's Icarus-like career in the saddle for his father, George. “As a supposed 16-year-old in '45, he finished among top apprentice riders in North America.”

Grisham's “supposed” does a lot of heavy lifting, for the minimum age for apprentices back then was 16.

“However, in those days, it was possible for an underage youngster to get by stewards and begin riding before turning 16. There is reason to believe Hazleton might have fallen into in this category. It is a matter of record he emerged a riding star at Arizona tracks and Caliente. One nine-race card at Caliente, he rode six winners, two seconds, and a third during a single afternoon.”

The melting sun to Hazleton's Icarus dream was biological. “Increasing weight soon terminated his saddle career,” Grisham noted, with blunt assessment.

What happened then depends upon the bard.

One version is that Hazelton returned to his studies in Phoenix, where the natural athlete became a prep school football star. Another is that he became a mainstay of the Southwestern rodeo circuit. Either way, it wasn't long before the Stetson-loving Arizonan turned his hand to training. Some reports pin the date as late as 1957. A tattered win picture from 1948 lists Hazelton as the trainer.

“After struggling for a while to saddle his first winner, the day finally came in Silver City, New Mexico. But Richard would have to wait until he was 26-years-old for his first 'bread-'n-butter' horse, a $500 claimer named Foxation,” one profiler made of Hazelton's early years with a license.

The box yields precious little of Foxation but considerably more of Zip Pocket, whom Hazelton saddled in 1967 to a 5 1/2-furlong world record of :55 1/2. The following year, Zip Pocket set a world record of 1:07 1/5 for three-quarters of a mile.

“Was it because of the biochemicals sprayed on the track or is Zip Pocket really that fast?” asked writer Pete Peters, after the horse's winning appearance at Turf Paradise.

Peters, a brylcreemed pipe-smoking staff writer for the Gazette, had the full-faced appearance of someone with limited athletic inclination. This is in stark contrast to the typical Hazelton runner, jettisoned into racing folklore as though shot from a cannon.

“If Hazelton trains 'em… he's a runner…” one observer described it. An early example was the Rudy Krize-owned “speed-geared grey colt” Wandering Boy, who came out on top in a $3,500 winner-takes-all duel at Turf Paradise against the Quarter Horse, Arizonan.

The clippings bear no date, but given how weathered is the tissue-thin newspaper, the late 1960s seem a safe bet. The following decade the trainer stepped it up another gear, with much of his success hinged upon bringing an army of horses West to East before commandeering the Chicago claiming circuit to make room for fresh legs.

“Contrary to rumors, Richard Hazelton did not suggest this dinner. Hal has claimed 11 horses off Richard this year and won only one race with the sum total,” said trainer Bill Resseguet, at a dinner–which sounds more like a roast–organized by the Chicago chapter of the Horsemen's Benevolent and Protective Association in honor of trainer Hal Bishop.

“I realize Richard is most appreciative of unloading those 11 horses,” Resseguet deadpanned.

The observation, though couched in jest, provides a useful entry point into the subject's character.

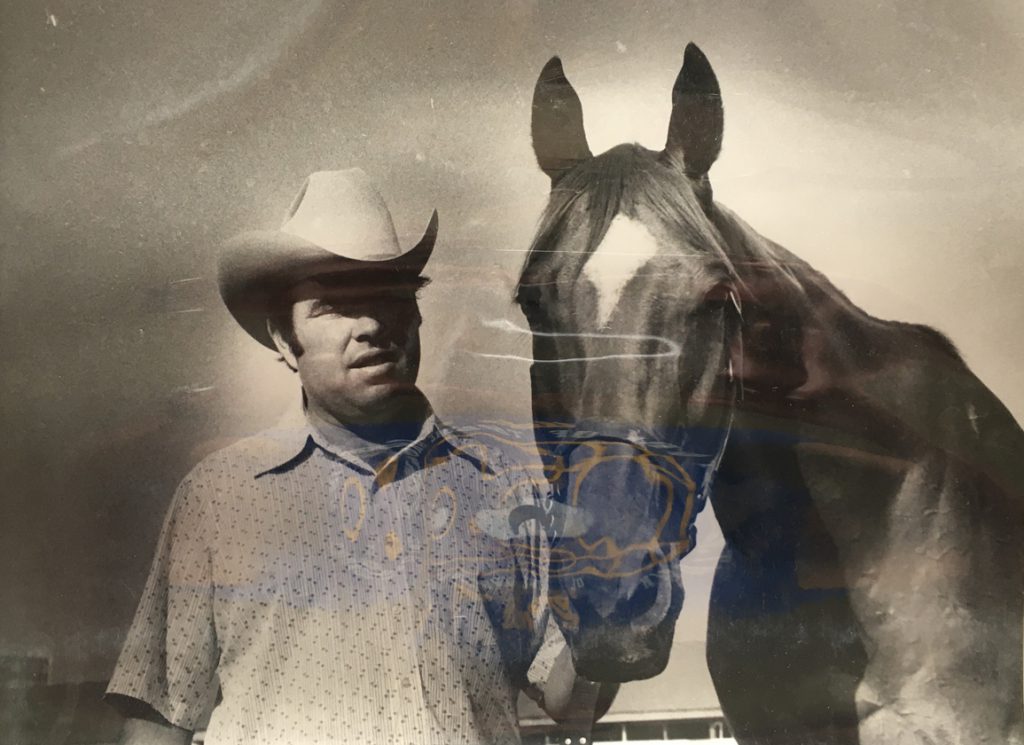

On the one hand, Hazelton is made as inscrutable as an IRS inspector.

“Husky,” one scribe calls him. Another, “a man of few words.” “Taciturn.” A “dark-browed horseman who prefers boots and Stetson.” And a “modest wonder man from Arizona” with “his ever-present cowboy hat and slow Western drawl.”

Yet ambition doesn't run on empty fumes alone.

To the Chicago Sun-Times, Hazelton let slip the mask. “It's been a difficult job,” Hazelton said of plans to reach 5,000 wins, “but I have been averaging approximately 134 winners a year so maybe in the year 2001 I can brag of what I did in less than 40 years.”

The pipe-puffing Pete Peters managed to elicit from Hazelton another rare peek through the same slim aperture. “I finally landed him,” crowed Hazelton about the wealthy businessman, Harold Florsheim, who Hazelton lured to his owners' ranks for the 1966-67 Turf Paradise racing season.

“I've been after him for a long time but I couldn't convince him to come West with his horses,” Hazelton added. “He finally consented. He's got some good stock.”

Modeling the trainer's work ethic, Don Grisham at Sportsman's Park turned to a quote of Hemingway's: “You got to learn something: Never confuse movement for action.”

As Grisham put it, “There is always tote action on Hazelton-trained horses. As for the movement, Hazelton was in Kentucky Friday to inspect yearlings with Harold Florsheim, the shoe magnate. He jetted back in time to saddle two winners on Saturday's card, including Glory Run in the $22,425 Crete Handicap.”

In her husband, Marge Hazelton–a champion calf roper and an integral part of the story–saw an “uncanny ability to remember all the horses on the grounds and what they have done in each of their races. His memory helps him put our horses in races in which they have a good chance of winning.”

With her husband's ego evidently in mind, Marge added: “He can't remember anything else, of course.”

Then comes Dr. Richard Radke, the former orthodontist and a key patron of Hazelton's over decades.

Radke believed his trainer of having “one of the highest IQs of anyone I've ever met, but not many people are aware of that because he's so modest and quiet,” or so he told John McEvoy of the Daily Racing Form.

Hazelton's parsimonious approach to shared connection had some unintended side effects.

“There have been a few times that we didn't have the best communication,” Radke added, warmly. “Times like when I'd call up Richard and ask about one of my horses, and Richard would say, 'Oh, I sold him for you. I guess I didn't call you about that.'”

Given how often the search for a father's approval launches the hero's journey–or so says Joseph Campbell–perhaps the most telling insight is from Hazelton's own tongue, shared on the back of a Sportsman's Park program in a potted bio in which we also learn the trainer's favorite food (steak) and favorite movie (“Shawshank Redemption”).

“I'm very proud of my father, George. He was a real 'man's man',” Hazelton said. “He had that rare ability, I think we call it charisma, to draw people to him.”

“Arlington builds a great deal right around you”

Where naval gazing has now become all but a national occupation, Hazelton offers a refreshing alternative, one very much of its time, when exterior interests held almost exclusively one's private inward-lit gaze.

The box is a sobering reminder of this at a time when it can feel as though the coattails of horse racing have snagged on some fast-moving bullet train, dragging it forward to goodness knows where, bumping and somersaulting, never able to quite get its footing. For it is not lost how Hazelton's favorite playgrounds are now an aberration of his memory–Arlington a tumbleweed ghost town and Turf Paradise a derelict disgrace.

So, why not turn to the architects of this collection of halcyon summers for advice on where indeed to tread now–people like Richard Duchossois, then Arlington's chairman when in May of 2011 he wrote to Hazelton the sort of letter one imagines rarely escapes today's sterile racetrack boardrooms.

“We are delighted you have returned to Arlington,” Duchossois wrote, when the trainer had all but stored away for good the stable's shingle. “You are one of the staples of Arlington and Arlington builds a great deal right around you.”

He wasn't wrong–a good deal right was built around Hazelton. And so, after all, maybe it's okay if the box contains only a sliver of the great arc that constitutes a life greatly lived, just as long as every now and then such memoirs are unearthed, rediscovered anew, spread out across the floor in the evening lamplight by the kneeling archeologist with a lump in their throat.

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.