By Chris McGrath

Nobody, we keep telling ourselves, remembers a time quite like this. And that's true even of John Williams, who has seen just about everything in our business. But he did once experience something pretty similar–worse, if anything, strictly in terms of the springtime routines of a stallion farm. That was when Caro imported a wildly contagious venereal disease from France to Spendthrift, and the Department of Agriculture wanted to put a chain on the gate.

Williams imagined that he'd already fulfilled his most stressful task, in boarding a plane to Paris with a cheque for $4.2 million in his pocket. After bringing Caro to Kentucky, however, the world's premier stallion roster could only be kept in business if everyone in the breeding shed wore surgical hoods, gowns, boots and gloves.

Every square inch was disinfected and quarantined. As it happens, Williams gave his time to this project long before the current crisis. But however rare the precedent—whether in the quality of horses and horsemen, or in the dramas that colour their lives—you will find some guidance in the tapestry of a life too rich to be adequately unstitched here.

Perhaps the best measure of his wisdom, integrity and charm is the single compliment that might overcome his dread of flattery. For his regard for the dignity of the office is such that Williams would be pleased, mighty pleased, still to be simply acknowledged as a good horse-groom.

“Bill Haun instilled this in me,” he says, recalling one of the mentors of his Maryland youth. “That the most important person to the horse is not the trainer, not the owner, but the groom who lives with him. On the racetrack, I loved being with some more than others; but I loved being with all of them. I'll never forget rubbing a horse called Tara Host. They claimed him at Monmouth Park. And I'm coming back with the groom leading my horse to another barn, and trying to get him to understand: he can't blow the dirt out of his eyes, he doesn't like it, and all the things I knew about him, as we're going back with this bridle in my hand and crying because I'd lost him.”

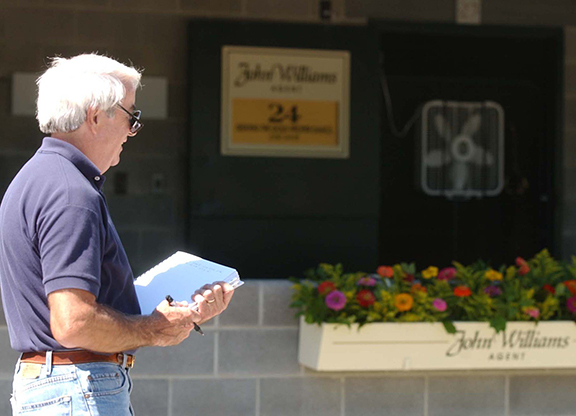

The snowy-haired septuagenarian before us remains in tandem with that young groom not just in brightness of eye or spryness of demeanour. He also has the constant prompt of a photograph, at home in Versailles, preserving his first ever visit to the winner's circle at the age of 24.

“Let's see,” he says. “This is April 5, 1966. The winner's circle at what is no longer a racetrack. Bowie, Maryland. With Edgar Lucas, the owner of Helmore Farm. I was working for this wonderful horseman Billy Haun. And here I am, with a mare called Compass Rose. Can you see how proud I was, to be standing in that winner's circle? I mean, you'd think we just won the Oaks. And Mr. Lucas, look how happy he is to win a $5,000 claimer. This is how much we loved it, even at that level.”

The young man in the picture had no immediate background in horses—though Williams is still maddened that the old equine remedies collated by an Irish grandfather he never knew, who came over with a draft of coach horses for a wealthy family in Philadelphia, were incinerated on his death—beyond a father who couldn't wait to close the barbershop in time to catch the daily double at Pimlico.

Yet Williams had only completed his first semester at the University of Maryland when switching his education to Pistorio Farm, outside his hometown of Ellicott City. Here he was blessed to encounter a veterinarian as communicative as he was sage, Dr. Irwin Frock.

Admittedly his first racetrack employer did not prove quite so exemplary, but the time and place were propitious: that was the year the memorable Horatio Luro, his hat tilted just so, came to town with a colt they reckoned no more than 15.2hh.

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.