By Robert D. Fierro

The most frequently asked question your correspondent and his associates answer about biomechanical efficiency is (paraphrased) “What component, or combination of components, of a horse's mechanics other than speed is most likely to tickle your fancy?”

After almost 40 years of evaluating thousands of horses from four continents this is how we answer the question with some facts-those facts being actual race records. What better way to go about this than to assemble a test group of peers and apply those suspicions to that group?

Thus, for this study we selected a combination of the two factors that project the efficiency of a horse's stride mechanics-stride extension and stride rhythm-which are often not apparent to the naked eye based on conformation, walk or even breeze. In short, that's what tickles our fancy.

With those two factors isolated, we then decided that the perfect test group would be virtually every winner of a Triple Crown race from 2000 through 2018 (37 are in our database). We figured that if we can find commonality of stride characteristics in this group then we might be able to convert anecdote into to realism.

First, let's get some definitions out of the way.

Stride Extension: This component reflects how well a horse can extend its stride length without interference biomechanically. It takes into consideration several factors relative to the horse's height and various body lengths which tell us if the horse might be better at sprints or over a longer distance. A horse with less than adequate extension runs the risk of interfering with itself and/or not being able to recover quickly if it runs into trouble. If a horse has very good power and leverage through its rear end components, however, it can overcome inadequate extension, but this is generally a rare occurrence.

Of the 37 Triple Crown race winners we examined, 33 (89%) had fairly good to excellent stride extension, four (11%) poor. Three of the four with poor extension, however, had excellent rear power and leverage mechanisms, and the other one was basically a one-paced galloper who needed to stay out of trouble, which he did mostly due to heady riding tactics.

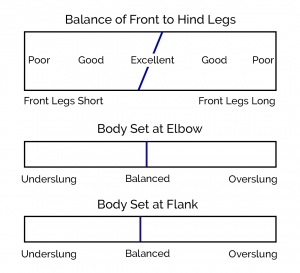

Stride Rhythm: This component determines how leg length and body-set are likely to work with, or against, each other during a race. Legs go through an internationally accepted standard growth curve between 30 and 48 months and in some cases the front legs are much shorter than the back, or vice versa, at 30 months but grow more equal at 48 months (or vice-versa).

The body-set of a horse is determined by the measured distances between the horse's elbow to the ground and the stifles & flank to the ground. The body-set indicates how it may perform more efficiently and is usually described as either “square,” “downhill” or “uphill.”

A square body-set with equal leg lengths indicates the horse is likely to be able to handle most distances on most tracks. Horses that are also a bit low to the ground with short front legs or a bit off-the-ground with longer leg lengths are also basically square. These distinctions are best explained in a series of graphs below.

The illustration is of a horse whose leg lengths are projected to be equal at 30 and 48 months (top of the box is 30 months) and whose body-set is square. This horse won the Preakness in the 2000s.

Body-set which is “off the ground” may allow an efficiently made horse to handle sweeping turns and longer distances depending on leg length. The combination can enable a horse to leap to the lead early or settle back and wear them down. The illustration below is of a horse that won the Kentucky Derby wire-to-wire in the 2010s.

Downhill horses can be basically square but a bit low at the elbow and short in the front legs. Generally, this is the profile of a front running miler or a horse which needs to settle and build momentum around two turns. Below is an illustration of a Kentucky Derby winner in the 2010s who was able to use his speed to become a multiple stakes winner up to a mile on the head end but was also able to relax around two turns and steal a race like the Derby when his reserved energy and power kicked in late.

What we did not find among these Triple Crown race winners are horses whose body sets and leg lengths were–how you say?–confused. Here are two examples of horses that were sold as yearlings in 2017, one for over $600,000 and the other more than $200,000.

Below is a filly who is low to the ground at the elbow with very long front legs. The likely result would be that her front legs would come up too far while her front end would want to come down-some would call it high knee action. She made one start and was unplaced.

Below is a colt who is well off-the-ground fore and aft but whose front legs are quite short. Thus, while his body has a lot of ground beneath it, his front legs would not have the length or trajectory to coordinate with that body and they would likely “pinwheel.”

The bottom line here is that while there are racehorses that win good races regardless of their overall biomechanical profiles but it is more likely that they can win the big prizes if they're able to efficiently extend themselves and–with apologies to George Gershwin and Ethel Merman–if they've got rhythm.

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.