By Emma Berry

We've never had it so bad, apparently. That of course depends on whether you're a glass-half-full or half-empty kind of person. Mine has been mostly empty so far in 2024, of the good stuff at least, but the swapping of a decent claret for chai tea has not lowered the spirits as much as might have been imagined at the start of January. In fact, optimism levels are running high in this very small corner of Newmarket at present.

For a start we have made it through storms Isha and Jocelyn with the loss of only one roof tile and a fence panel. There were no loose horses or fallers, and there has been no ice under the hooves of the fresh horses just back from their winter holidays. These sound like minor considerations, but in a small stable, when the horses who live below and the staff who come in every day to ride them feel like family members, every day that passes without dramatic incident is a good day.

Don't get me wrong, I don't skip around every minute of the day being irritatingly upbeat. I have grave concerns over the way racing is heading in some areas, particularly that so many people seem willing to gamble on trading horses but have no interest in racing them. With little acknowledgement of their importance to the Levy, the paltry level of funding for lower-tier races is making it increasingly unsustainable for many of the sport's smaller participants to continue and is in part deterring others to get involved. It is becoming harder not to conclude that there is now no place for the small breeder, the small owner or the small trainer with their lesser horses. That would be a shame.

In the long history of sport, fans have deified the very best, and rightly so. We all need a Pele, a Piggott, a Klopp or a Cecil to sprinkle a little magic. But the sporting public also loves an underdog. Only recently, the exploits of Hewick on Boxing Day reminded us of this. And I long to see another horse of the ilk of Sergeant Cecil or Speciosa in the hands of trainers whose talents lack only the supply of horses.

For a start, what a story. Fresh faces, a new narrative. And then there's the knock-on effect; the hope brought to others in a similar situation, that encouragement to roll the dice.

Racing has always been built on dreams. People come and people go, and new people replace them with that same old dream. Retention is important, of course, and it is hard not to look upon last week's announcement from Andrew and Gemma Brown of Caldwell Construction with anything other than concern. Here are owners who have enjoyed major success, with some exciting young National Hunt prospects on their hands, withdrawing from racing and dispersing their stock, apparently following three recent fatalities among their string. One can sympathise with the Browns while wondering how long jump racing will be tolerated by the general public, particularly in Britain.

Among the other issues of the day are prize-money, concerns over Britain and Ireland becoming nurseries for other racing nations with deeper pockets, and the hoovering up of top-class stallion prospects by our friends in Japan. Well, guess what. None of this is new.

'No Racing and no Money as 1968 comes in' ran the cheery headline on the editorial leader in the February 1968 edition of Stud And Stable. Britain was then in the grip of a foot-and-mouth epidemic which had halted racing during the previous December (the same disease later caused the cancellation of the Cheltenham Festival of 2001). Remarkably, the December Sales of 1967 had been permitted to go ahead by the government under strict protocols and they recorded some notable returns despite some epidemic-enforced withdrawals. Sound familiar?

Vaguely Noble sold for a record 136,000 guineas, and he was far from the only high-priced lot to fall into the hands of owners from overseas.

The gloomy leader stated, “Already supported by racing programmes that justified the payment of high prices, French and American buyers were afforded a field day.”

It continued, “Throughout the century, England and Ireland have acted as a storehouse from which to supply the world's Thoroughbred requirements. This year's December Sales raised more dramatically than ever the question of how long we shall be able to go on doing so unless we can increase our prizes and keep the best at home.”

These words, written 56 years ago, could so easily have been penned today.

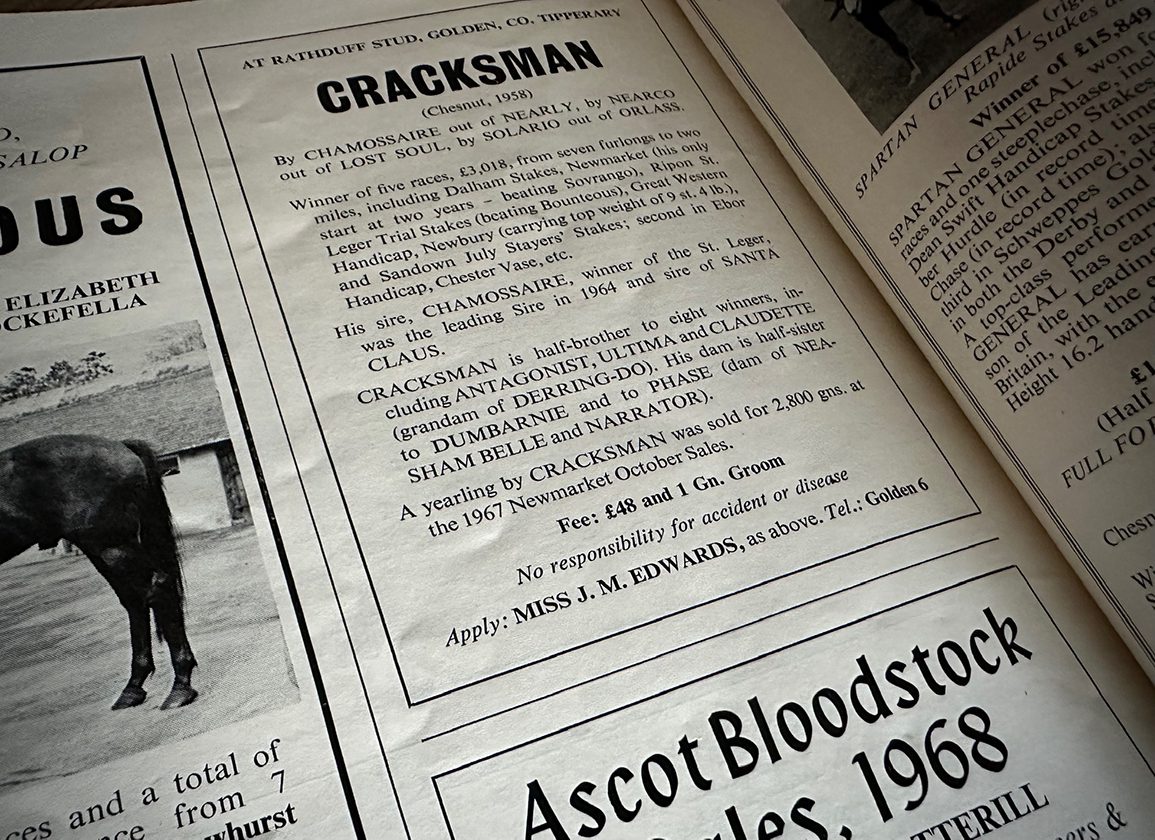

Elsewhere in the same magazine there was a short report on the sale of the stallions Larkspur and Hard Ridden to Japan, which began, “Following on from the rather alarming foreign purchases of the top lots at the Newmarket December Sales comes news of the export to Japan of two Derby winners.” Again, this has a familiar ring of recency to it (as did an advertisement in the same edition for Rathduff Stud's promising young stallion by the name of Cracksman).

In fact, the only thing that felt a little different in this edition of Stud And Stable from 1968 was a photograph of the packed stands at the Curragh in an advert for the Irish Sweeps Derby which boasted of the higher average prices of yearlings with Irish Derby entries. Just don't tell Patrick Cooper or he might write another letter.

Over the years we have had epidemics of the human and bovine variety temporarily halt racing in its tracks. It would have felt catastrophic at the time, and the worry of the months of April and May 2020 in particular is still fresh in the mind.

Somehow, though, this industry bounces back, often stronger than ever.

Racing limped on, restricted and reduced, through the far graver years of the Second World War. The Derby and the Oaks were run at Newmarket, but at least they took place. It must be said that the influential owner-breeders of the day played a major role in persuading the government that a certain amount of racing must continue for the morale of the people, not to mention the important continuation and testing of the breed on the racecourse.

And yet even in those desperate times we find in the Bloodstock Breeders' Review similar buoyancy at the sales, which is quite staggering considering what was taking place in the real world. A report written in the sixth year of war concluded, “Bloodstock Sales in 1944 showed the highest aggregate ever known…The December Sales results alone beat all hitherto established records…The same story is to be recorded regarding the Dublin Sales. All records were surpassed by the results in 1944.”

I've lost track of the times I've reported on a “record-breaking” sale over the last decade. Of course the vitality of the bloodstock market should not be confused with the overall health of racing. As stated, an increased number of people treat the sales like the stock market and are not involved beyond that, while plenty of money that changes hand comes from foreign investors.

That's not all bad though. We have always needed international interest in our bloodstock market, and the breed itself needs it. Many of those investors hail from countries which are not conducive to the breeding and rearing of horses, and the fact that the green and pleasant lands of Britain and Ireland are ideally suited to that pursuit has not gone unnoticed by those from overseas who have decided to establish their own breeding operations in this part of the world.

And yes, to a degree, it is facetious to imply that little has changed. Glancing through those old books and magazines, the most telling difference is that there were once so many small, independent studs that each stood a stallion or two. Now, many have been subsumed by those major investors whose breeding operations have become empires. Whether that is good or bad is almost a moot point. It's different, but we still have the choice of a large range of stallions, with many of the best in the world standing in these isles.

None of this means that we can simply think all is well and turn to complacency. Those quickly expanding racing programmes in the Middle East will need more and more horses to meet their demands, at a rate and standard which exceeds the potential of their local breeding industries. In part that is good news for European breeders, but it may well prove detrimental to racing here.

A personal gripe is how much owners appear to be encouraged to sell on a horse as soon as it shows a glimmer of talent. Obviously lucrative offers are hard to turn down, and horses can suddenly be lame in the blink of an eye, so this isn't pointing the finger of blame at anyone who has cashed in. But what happened to that dream? Isn't it what drew people in in the first place, the chance to race a top horse?

There really is nothing like the thrill of being connected to a winner, whether in a syndicate or as a sole owner-breeder. That's the dream we should be selling, for no get-rich-quick scheme can equal that high.

The politics of racing can certainly detract from our enjoyment of the sport if we let it. So it's time to stop doom-scrolling. Put down your phone and get yourself out to a paddock or a racecourse to marvel at the beauty of the Thoroughbred. The start of the Flat turf season is now but two months away and the foaling barns are once again filling up with the stars of the future.

If we get it right now and treat these wonderful creatures with the respect they deserve throughout their lives, then there is hope that in another 80 years the bloodstock journalists of the future will be writing about yet more sales records and why the Irish Derby should remain at a mile and a half.

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.