By T. D. Thornton

When Gulfstream Park staged the “Race of the Century” 56 years ago this spring, 17,300 fans packed the grandstand. They stared out onto a horseless track, where an empty starting gate was parked ceremonially at the 1 1/4 miles position. They rooted, cursed and cheered home their picks.

Not a single person ended up witnessing the race. Yet those in attendance–and a nation of fans who tuned in via the NBC Radio broadcast or read about the outcome in coast-to-coast newspaper coverage–seemed to be in vehement agreement for weeks afterward that the best horse didn't win.

The Race of the Century on Apr. 6, 1968, was a promotional stunt, the sport's first major attempt at using a computer simulation for a form of entertainment. It was also, in part, supposed to serve as a testament to the emerging–even intimidating–power of computing technology.

It might have been a bust on both attempts.

But if your barometer is the old marketing adage “even bad publicity is good publicity,” the event could retrospectively be considered a hit.

The imagined get-together of 12 of the greatest Thoroughbreds from different eras drew a decent amount of ink and interest in its day, and even today the concept of a “fantasy race” lives on. Every few years now in the 21st Century, as new fan favorites get added to the list of “greats,” the idea of a recreated showdown among epic champions keeps getting dusted off and repeated, powered by whatever latest and greatest technology happens to be in vogue.

In 1968, the entity that made its case for being the pre-eminent prognosticator of America's all-time historical horse race was a British technology team from the University of Liverpool's Department of Computation and Statistical Science.

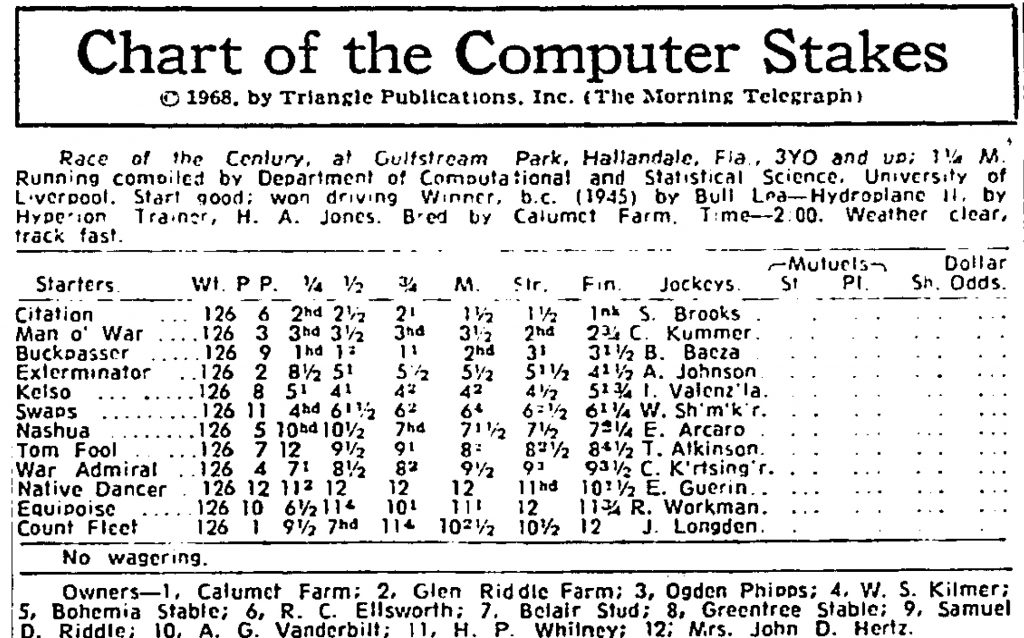

Several months earlier, a panel of 150 stateside sports writers and broadcasters had been tasked with voting on the 12 luminaries who would line up in the digital starting gate, and they came up with (in eventual randomized post-position order) Count Fleet, Exterminator, Man o' War, War Admiral, Nashua, Citation, Tom Fool, Kelso, Buckpasser, Equipoise, Swaps and Native Dancer.

There was some pre-race griping that the selectors had concentrated too heavily on horses who had competed between 1948 and 1968. Today we would say that a “recency bias” contributed to the lack of better representation from horses who had competed in earlier times.

First came the knockout…

In partnering with the British computing team, Gulfstream was riding on the tails of a publicity experiment hatched by boxing promoters and a Miami radio station that had featured a computer-generated “tournament” among heavyweight greats past and present.

That venture had drawn criticism because, somewhat improbably, all the highest-ranked dead boxers and all the Black champs got eliminated via computer, leaving the popular (and white and still-living) Rocky Marciano and Jack Dempsey to slug it out.

Both retired champs were conveniently hired on for promotional purposes. The underdog Marciano scored a surprising “knockout.” Muhammad Ali ended up suing the promoters for $1 million in damages because he claimed his reputation had been tarnished by losing to the ghost of Jim Jeffries.

As columnist Robert Lipsyte explained in the New York Times, not many in the boxing industry seemed concerned that the computerized championship had come off like a badly scripted pro wrestling match. “People within boxing were not terribly exercised about the tournament,” Lipsyte wrote. “They are respectful toward anyone who can come up with a gimmick to make a buck, and are generally tolerant of fixed fights.”

In racing, presumably, there would not be as much acceptance for outcomes that were more orchestrated than computed.

Britain had already had a brief go at accepting bets on computer-generated racing in 1967, when bookmakers enlisted the help of programmers to stage “The Computer Gold Cup” after a bout of foot-and-mouth disease had shut down real horse racing for 40 days. Punters ended up not clamoring for that sort of action, and with the return of the real thing, simulated racing was cast aside.

It was against this backdrop that Gulfstream supplied the Liverpool team information about the selected horses' class, weight-carrying ability, and overall race records, and in turn the programmers fed that data into the computer. Final and fractional times, point-of-call margins, and winning margins were also included, but the computing team disclosed that those factors would not be given as much emphasis.

It took two full weeks to upload what was essentially past-performance data for a 12-horse field into the machine.

Man o' War's trainer, the then-84-year-old Louis Feustel, openly predicted the star colt who had won 20 of 21 races in the era just after World War I would “gallop” in the 1968 simulation despite the impressive credentials of his rivals.

“I'd have to fear Buckpasser a little. And maybe Citation,” Feustel told the New York Times several days prior to the event. “But Man o' War was the greatest. Even when he was walking or jogging, he wanted to get there first.”

Overwhelming fave…

Not many racegoers and turf writers disagreed with Man o' War's trainer. There was no pari-mutuel betting on the race, but Gulfstream had a pick-the-winner contest that offered prizes, and about 50% of the public chose “Big Red.” An estimated 40% of the published picks in the press also had him on top.

Yet some pre-race writeups tried to get inside the “brain” of the computer. Steve Cady of the New York Times took a contrarian approach in his handicapping by noting that despite setting American or world records at five different distances while winning under imposts up to 138 pounds, “An ominous note for Man o' War could be the emphasis placed on class of competition.”

Big Red's competition was practically non-existent late in his 3-year-old season, when he scared most it away and started favored at odds as low as 1-to-100 in six match races and four stakes that attracted only two other starters.

This, Cady reasoned, would count against Man o' War based on what reporters had been told about the computing methodology. The programming blueprint gave more credence to horses from larger foal crops who raced more often against larger fields.

Man o' War was made the (ridiculously high) 4-1 morning-line choice, with Count Fleet, who swept the 1943 Triple Crown, at 5-1, and Citation, the 1948 Triple Crown champ, at 6-1.

All entrants were assigned 126 theoretical pounds, and for the most part, they were “ridden” by the jockeys most associated with their prime performances in real life. The event was scheduled to be run prior to the first live race on Gulfstream's normal Saturday card.

When the race went off, the University of Liverpool team transmitted positions and margins to Gulfstream at five-second intervals, and it was the job of press box impresario Joe Tanenbaum to formulate that data into a narrative and call the race over the public address system and for NBC.

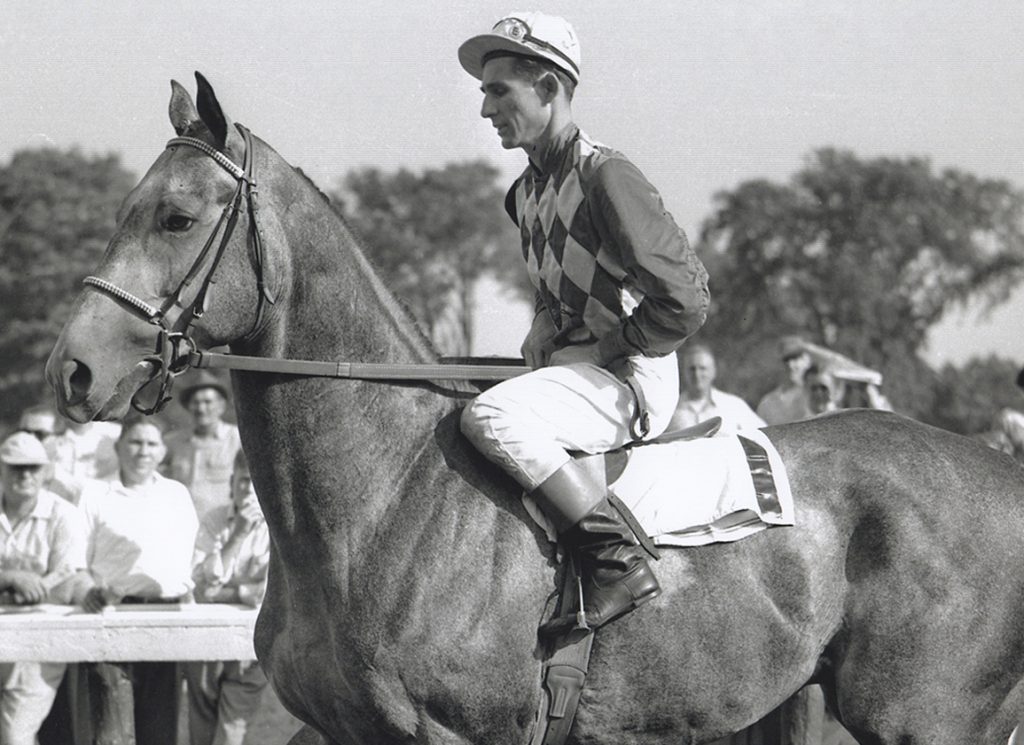

There was a gasp of disbelief from the masses facing the empty track when Tanenbaum announced that Braulio Baeza had sent Buckpasser to the lead. Buckpasser had just retired the previous season after being named a champion in all three years he raced, and the crowd would have been well aware that this audacious move was totally contrary to the leggy, elegant colt's standard off-the-pace tactics.

Buckpasser led by a head over Citation, with Man o' War stalking another head behind in third in the early going. Fans staring at the running order on otherwise blank closed-circuit TVs saw little change as the stalkers allowed Buckpasser to open up by two lengths entering the backstretch. The top trio held their same positions past the half-mile marker, but Buckpasser's leading margin had been sliced in half.

Around the far turn, Citation, the sport's first million-dollar-earner, swooped to the lead and now the main danger was clearly Man o' War, relentless in his pursuit and less than a length behind.

Big Red drove furiously at the smooth, efficient-striding Citation, extending his stride at a point in the race where jockey Clarence Kummer was usually easing him up in a romp. Man o' War loomed within a head 70 yards out, but Citation was emboldened by the challenge, surging under Steve Brooks to edge away by a neck at the wire.

Buckpasser hung on for third, ahead of Exterminator, Kelso, Swaps, Nashua, Tom Fool, War Admiral, Native Dancer, Equipoise and Count Fleet.

Aftermath, and beyond…

An un-bylined New York Times recap reported the results with a tone of incredulity.

“Although no press box handicapper would fault Citation, a number expressed the opinion that 'Man o' War must be spinning in his grave,'” the story stated. “One handicapper who had picked Citation confessed that he believed 'Man o' War would have run all those horses off the track, but when I saw the factors they were considering for the computer, I figured the answer would come out Citation.'”

Even the simulated two-minute winning time for the 10-furlong race came under criticism, with some turf scribes noting that it was a fifth of a second shy of the actual Gulfstream track record established by Citation's lesser-heralded stablemate, Coaltown, who did not even come close to getting voted into the Race of the Century.

Russ Harris of the Miami Herald wrote that “the manner in which the dream race was run created a broad credibility gap between the data machine and oldtime racing fans.”

Sports columnist Arthur Daley of the New York Times put it this way: “Computers are only as reliable as the information fed them. This one obviously [shuffled] through cards that had been folded, bent, spindled and otherwise mutilated. How else can you explain a front-running whirlwind like Count Fleet lagging all the way and running last? How else can you explain a come-from-behind charger like Buckpasser blithely stepping in front even though he always loafed once he was in the lead?”

Maurice Hymans, the linemaker for the race, agreed. “Buckpasser never went to the front. Can you imagine Count Fleet being outrun to the first turn by Buckpasser? Why did they have to go to England to do this? Don't we have computers in this country?”

Turf writer Sam Engleberg, described by Harris as a renowned speed handicapper, expressed a frustration that would resonate today with horseplayers everywhere.

“They ought to smash the machine,” Engleberg said. “Twenty years after he's dead, I lose a bet on Man o' War.”

Lipsyte, of the New York Times, was still writing about the Race of the Century four months after it occurred, and his column about computers and sports from Aug. 12, 1968, contained profoundly prophetic words about how technology would unfold over the next six decades.

Although Lipsyte did not use the term “sports analytics” that we now hear every day, he aptly predicted it.

“In the future, the matings of Thoroughbred stallions and mares will be completely directed by computerized information, and stroke analysis in golf, play analysis in football, and scoring in ski-jumping will be electronically aided,” Lipsyte wrote. “There is no reason, except money, why professional baseball and football teams could not have elaborate systems designed to pin-point weaknesses and call plays. As long as computers are programmed by human beings, sports can only profit, through increased efficiency and fewer injuries, from electronic coaching aids.”

Yet Lipsyte also warned of the ominous effects of an over-reliance on technology, both inside and outside the world of sports.

“The Machine, you see, will eat anything a man feeds it and will swallow everything,” Lipsyte wrote. “People who are fearful of such things as rifles, projectiles, unsafe automobiles and sharp objects are almost unanimous in their fear of The Machine. They are terrified that their one human characteristic, rational thought, will be borrowed, improved upon, and never returned.”

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.